Let your eyes adjust to the new colors, it just takes some time

2025

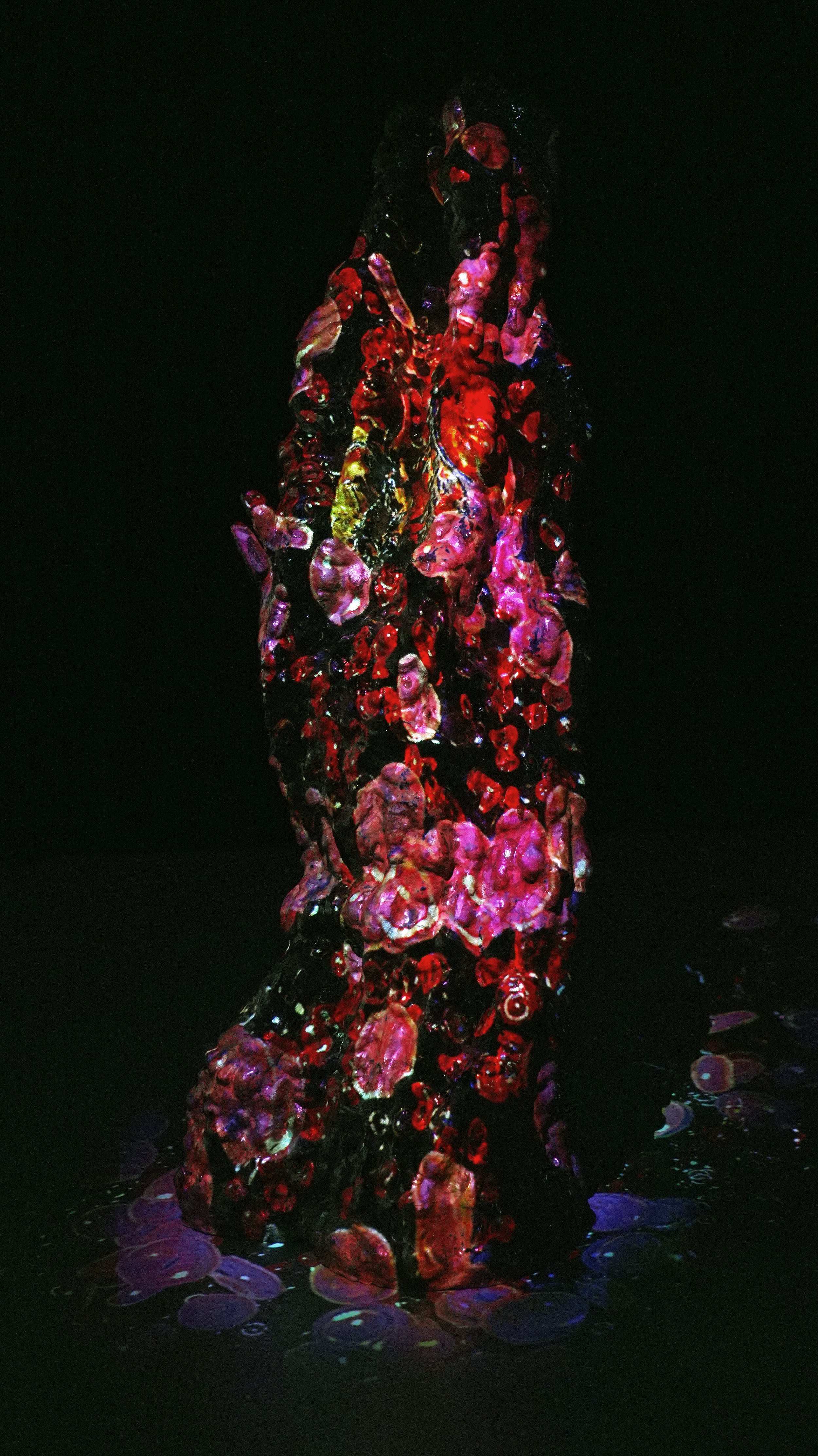

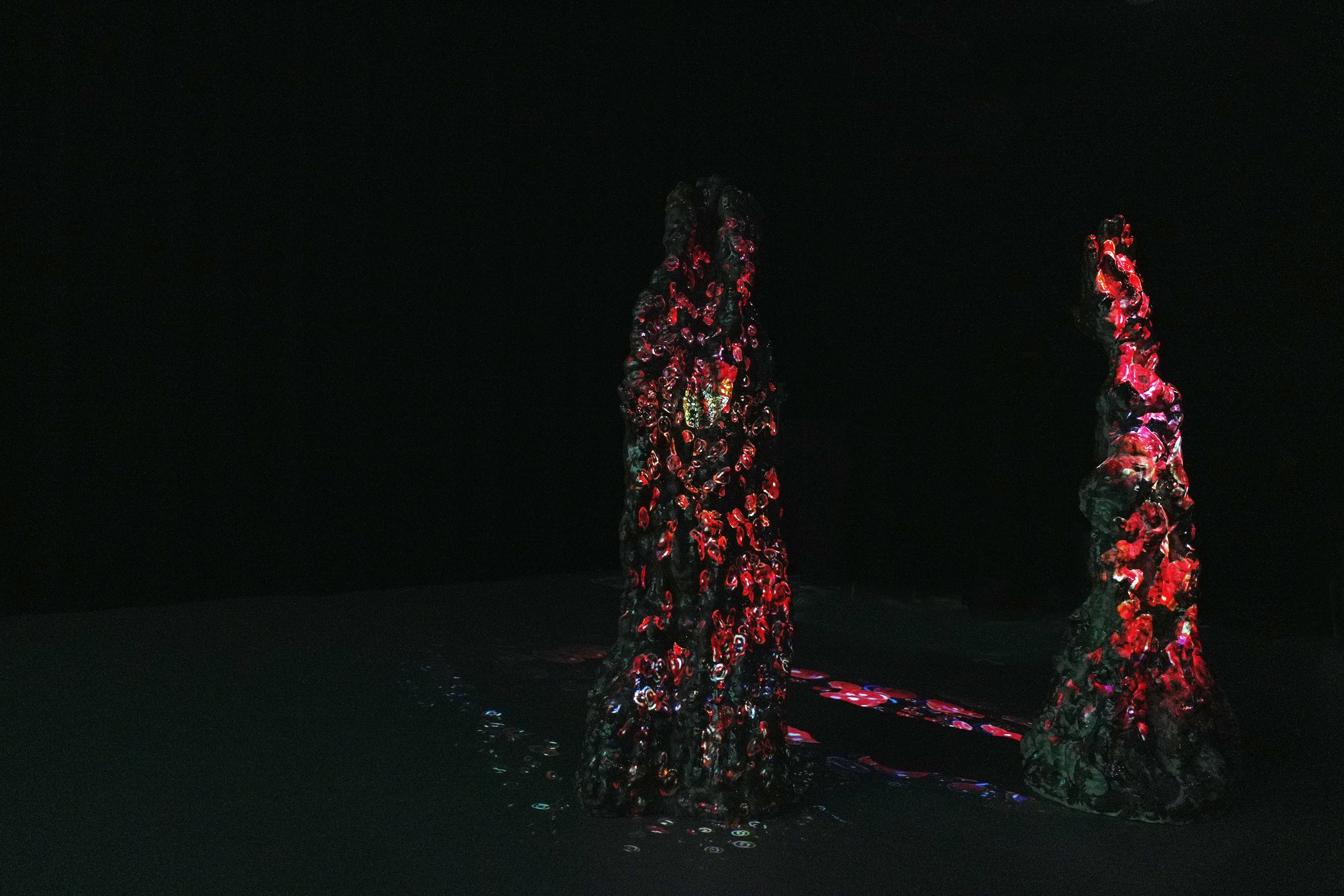

High-fired ceramics, 2 channel projected video, 10 min loop, multimedia installation with desk, freezer, heart rate monitor, water and ice, size varies

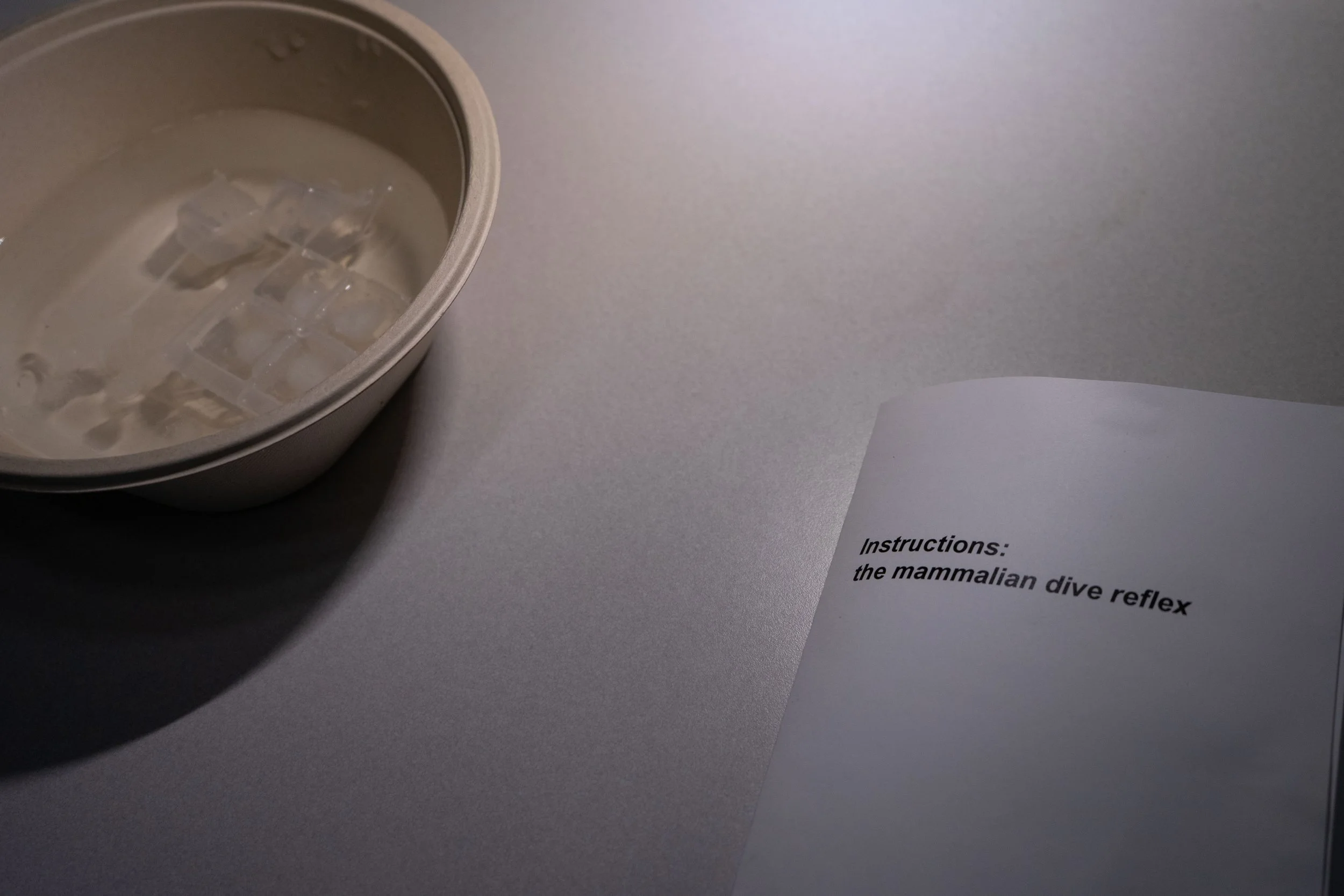

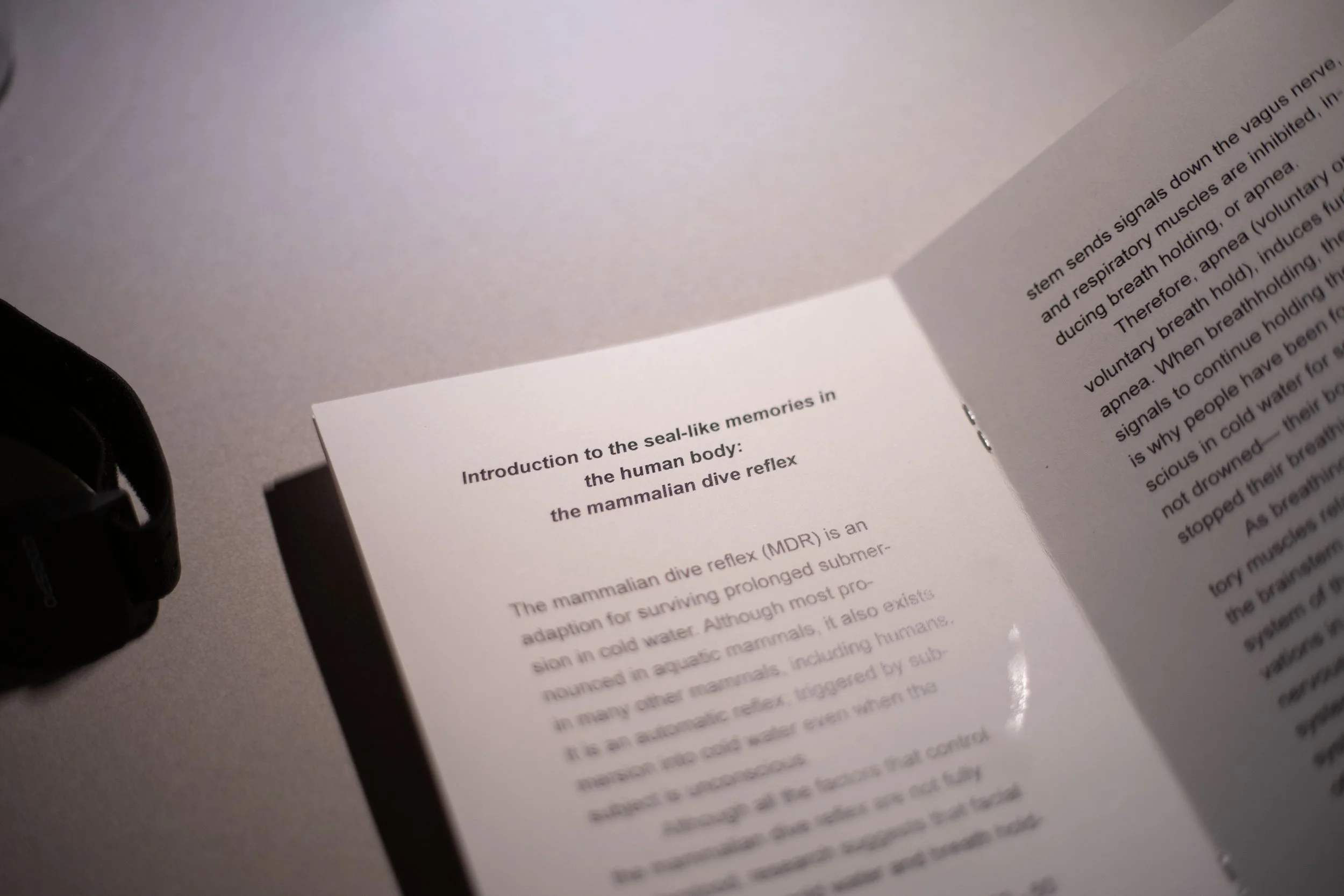

The mammalian dive reflex is a series of automatic processes in the body of many mammals, including humans, that prepare to survive prolonged submersion in cold water. When the face touches cold water, the heat rate slows, the outer blood vessels constrict, and the spleen releases red blood cells. This piece uses ceramics, animations, and interaction with cold water to explore the physiology of the mammalian dive reflex, and the affective experience of swimming.

Installed at the yearly iMappening show at the School of Cinematic Arts, University of Southern California, April 2025.

Special thanks to Carl Schmidt, Debra Isaacs, Stephanie Spray, Thomas Mueller, Farzan Sabet, Matt Pekarek and Nanci Lee.

Photographs by Tina Shi, Katie Luo, and myself.

At any coast— a river, a bog, an urban beach— the human always has the potential to swim. That is, they can change their way of traveling, can stop being vertical and start being horizontal, they can move through pushing and pulling rather than walking and driving. In water, humans typically have to stay at the surface to breathe air. And we always must return to the land. Like a ball thrown up in the air, we always return to the land from which we started from, following the laws of physics. Elementally out of place, the water challenges our bodies to survive in different ways than it survives on land. We are displaced, but we adapt surprisingly well.

A wetsuit, a pair of goggles, fins and hoods. These are the accouterments that assist with our transformation act. Without hair and necks, our outer skin monochrome black, our bodies suddenly become something more like a seal, or at least a flatworm. This is an alluring proposition, to transform into a water creature. I find it romantic, the ways that humans desire to inhabit places where we are (chemically, physically, physiologically) unwelcome. We invent exposure gear, vehicles, and apparatuses that allow us to enter these inhospitable environments like space and volcanoes. Perhaps it is the shift in milieu that we find to be so intoxicating, or perhaps it is the feeling of entering a waking dream, finding a new and unfamiliar reality.

This project arose from this interest in transformation. Through my own experience and research, I have learned that the act of becoming animal at the coastline is much more involved than wiggling into a wetsuit and strapping on goggles. The body itself is very wise. Inside our cells and our DNA, memories lie, latent and possibly forgotten. Memories of ancestors who swam more than we do, who swam more urgently. Memories of when we were something like a gelatinous sack, or a filamentous tube, or a fish armored with scales. To our ancestors, most of them anyway, swimming was a matter of life and death. Our bodies have evolved ingenious ways of coping with cold and immersion. Chemical recognition was born in our faces, sometime perhaps when we were closer to a seal than to a primate. Our bodies developed automatic responses to the feeling of cold water on the eyes, forehead and nose, triggering the spleen to release blood cells, causing the capillaries in our limbs to tighten. Our hearts learned to slow to a crawl, even during this moment of exhilaration, heavy exertion, and stress. In this configuration, our bodies are tightened in some areas, loosened in other areas, and the chemical hormones, receptors, nerve signals, and muscles all collaborate to use oxygen carefully, to prioritize the essential centers of the body— to pool blood at the heart and the brain, to disburse oxygen there.

The hands and legs grow cold and white, the chest spasms and hurts, but the center of the body is warm with chemical exchanges. The body transforms from the inside, in order to dive, just as we also physically transform to run, to fight, to make love, to sleep, to eat, to give birth, and to recover from an illness. Inherent in our DNA is an ever ready potential for transformation.

A few readings that informed this project:

Posthumanism by Rosi Braidotti

Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things by Jane Bennett

Waves of Knowing: A Seascape Epistemology by Karin Amimoto Ingersoll

Fast-Forward: Situating Post-Cinema by Holly Wilis

In Post-Cinematic Bodies: Configurations of Film by Shane Denson

“Video Installation Art: The Body, the Image, and the Space-in-Between.” by Margaret Morse

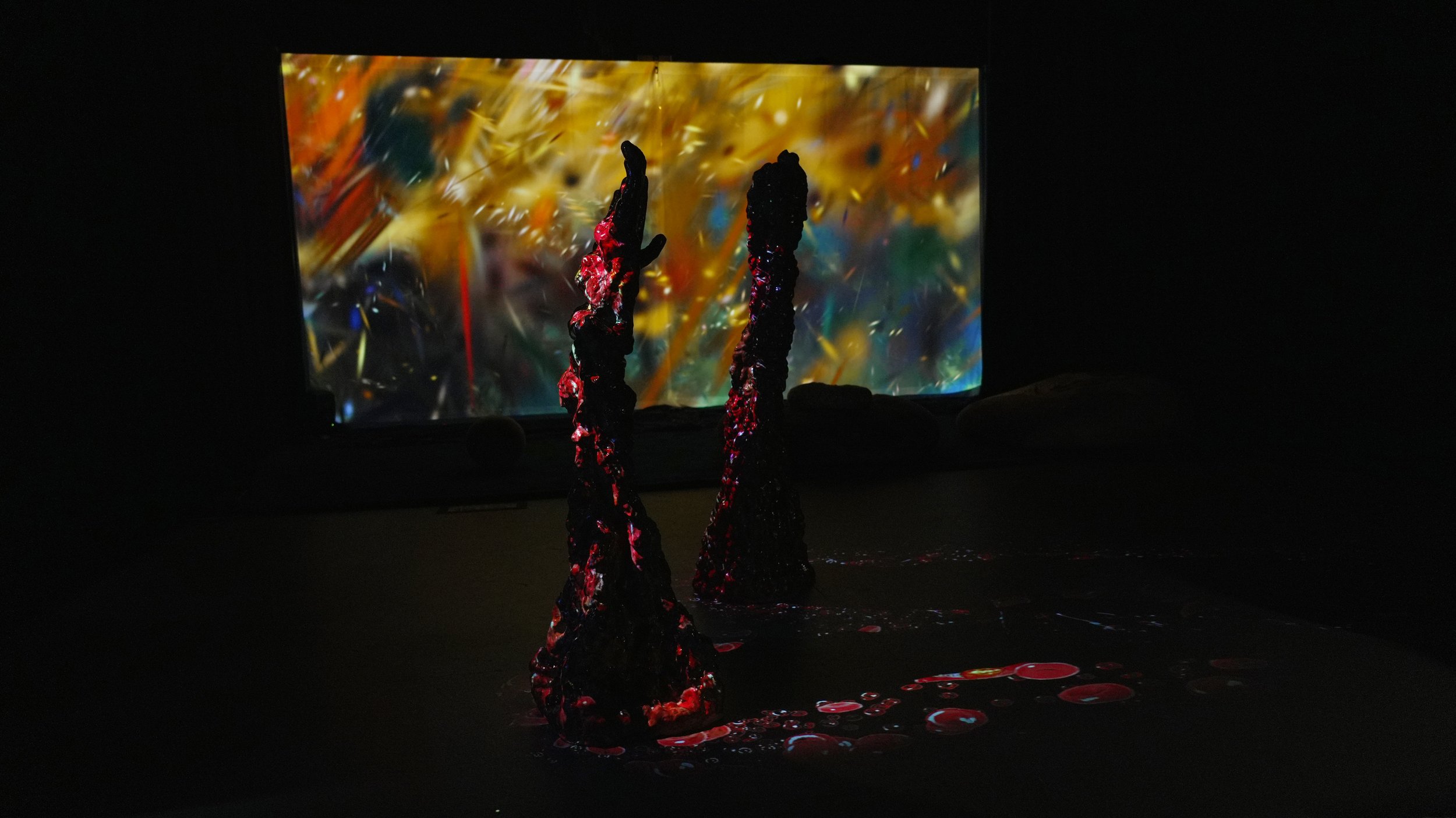

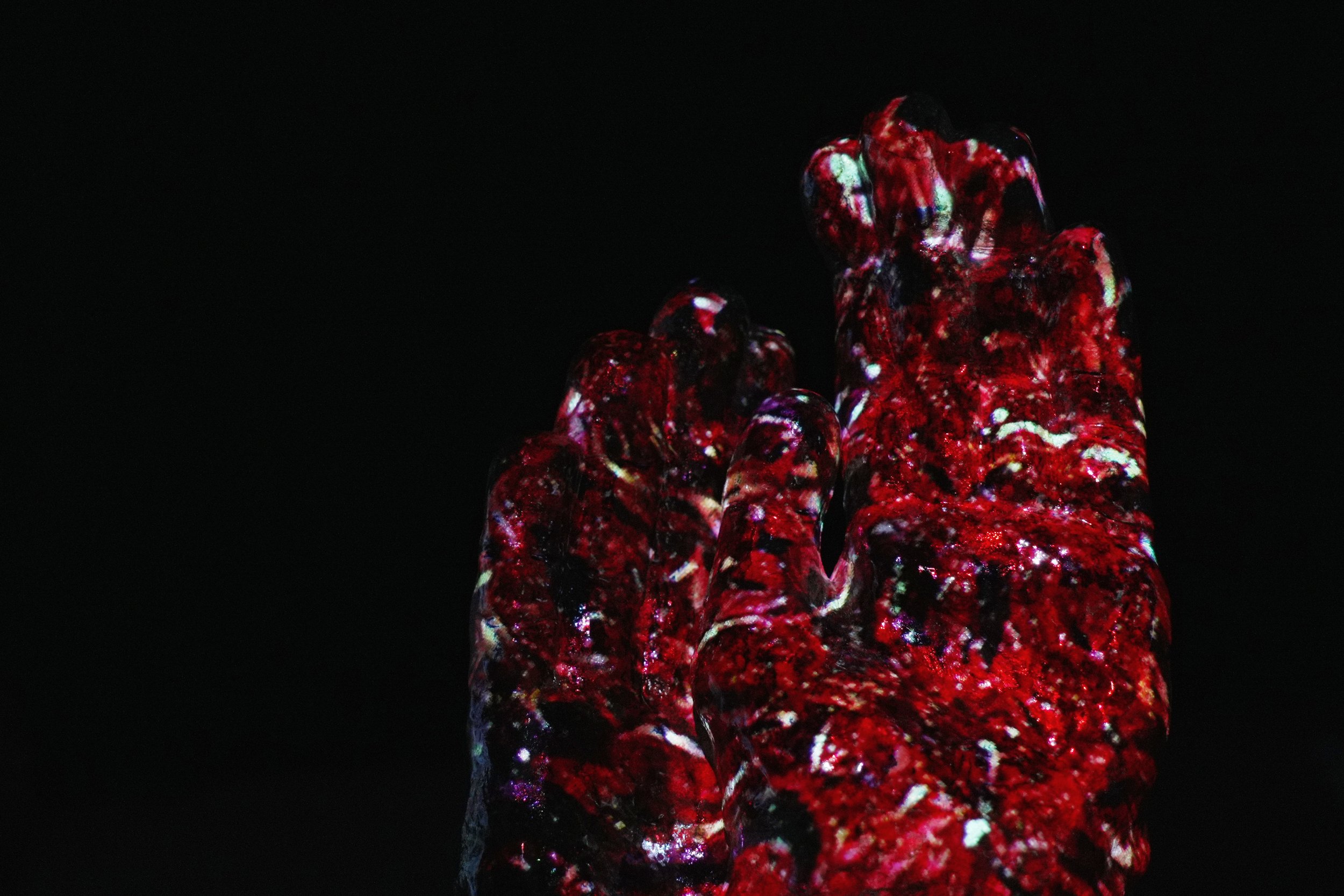

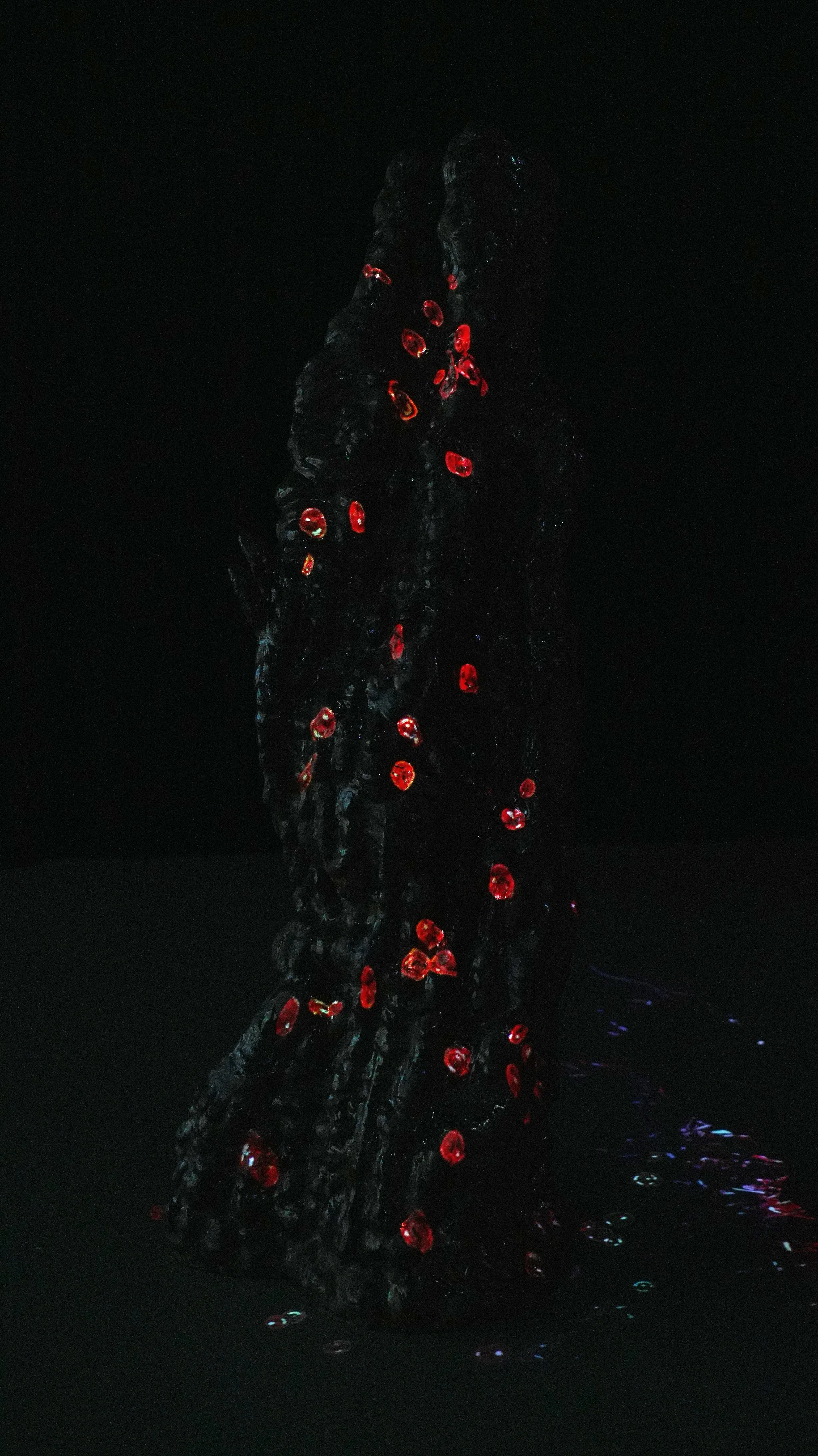

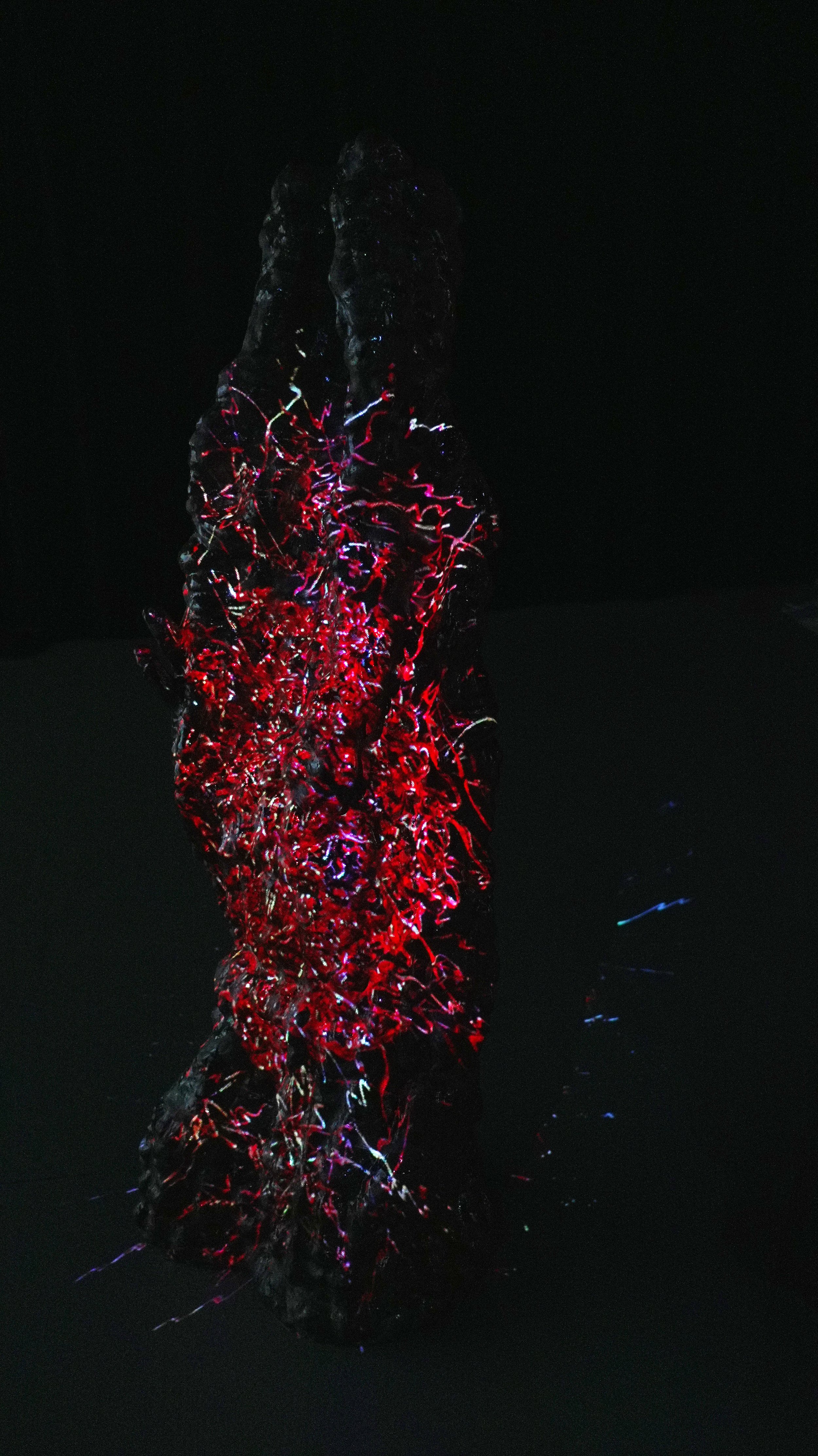

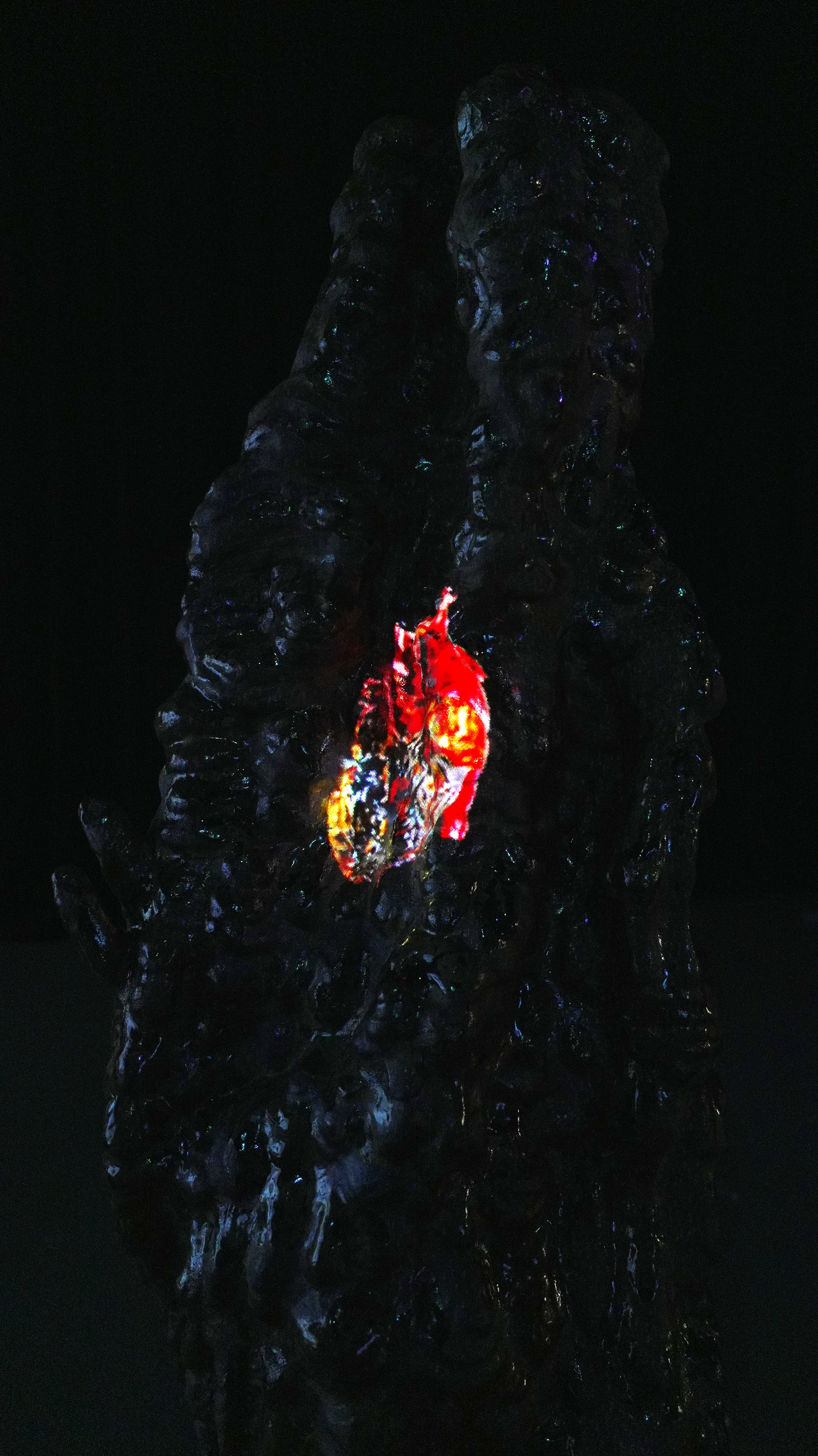

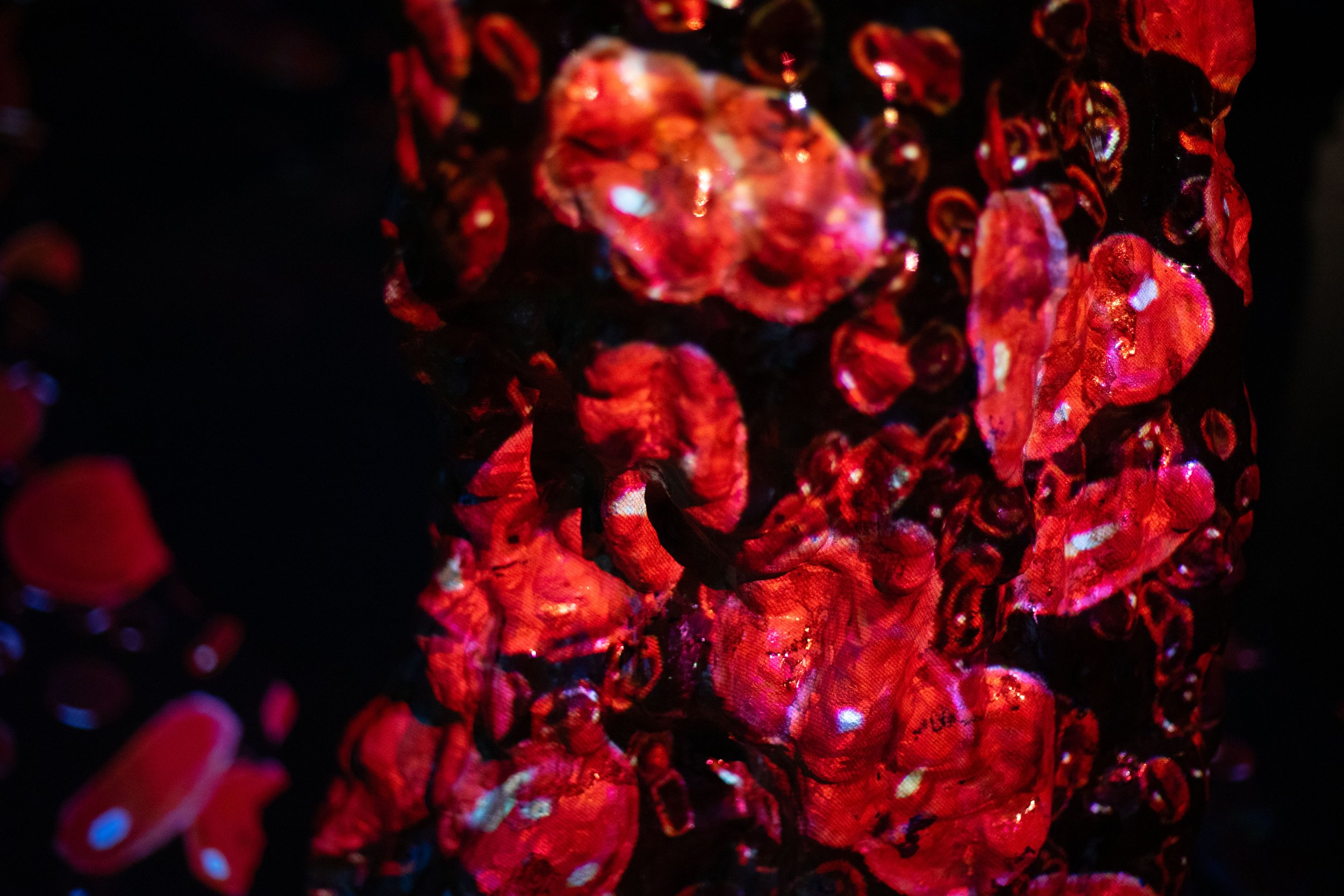

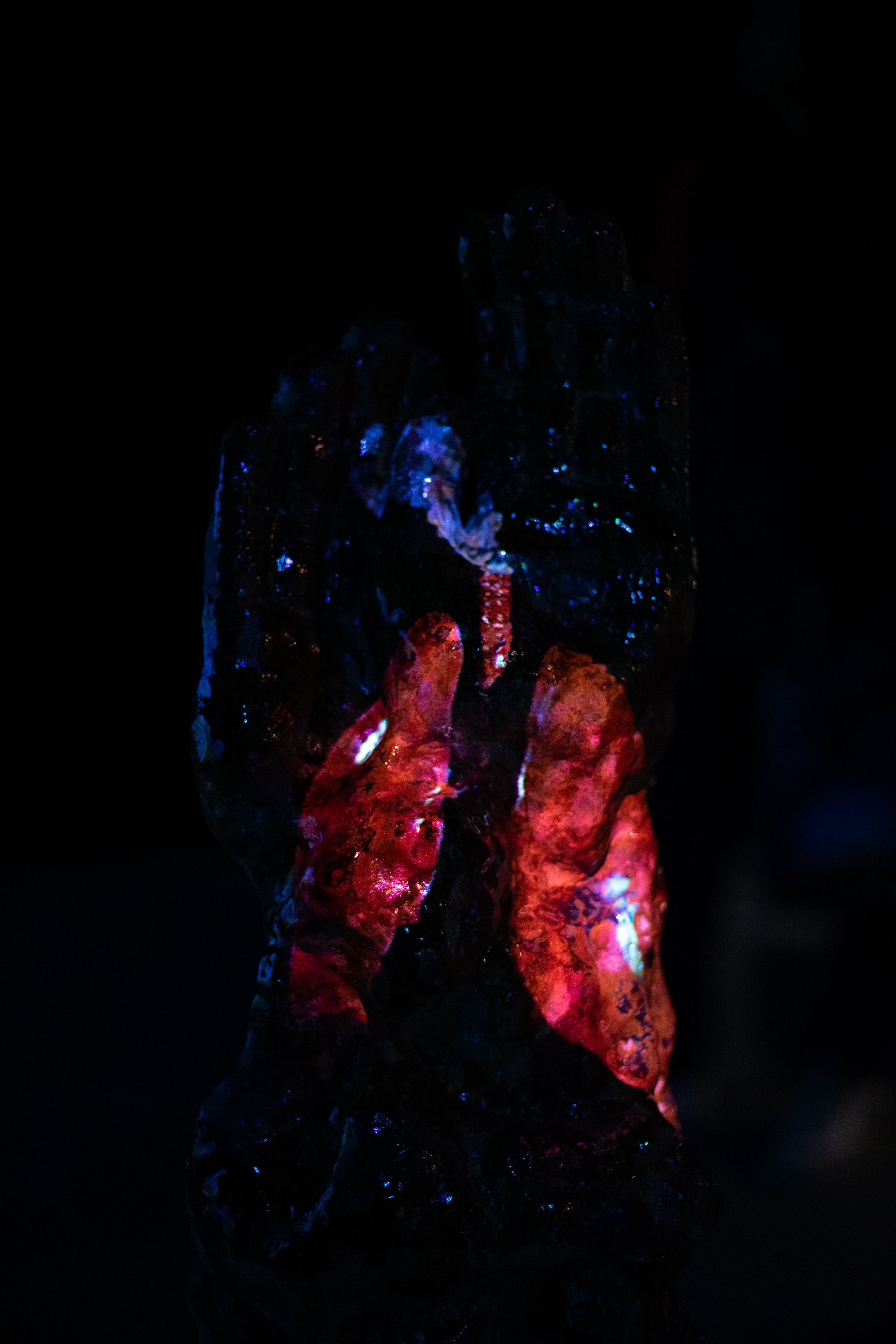

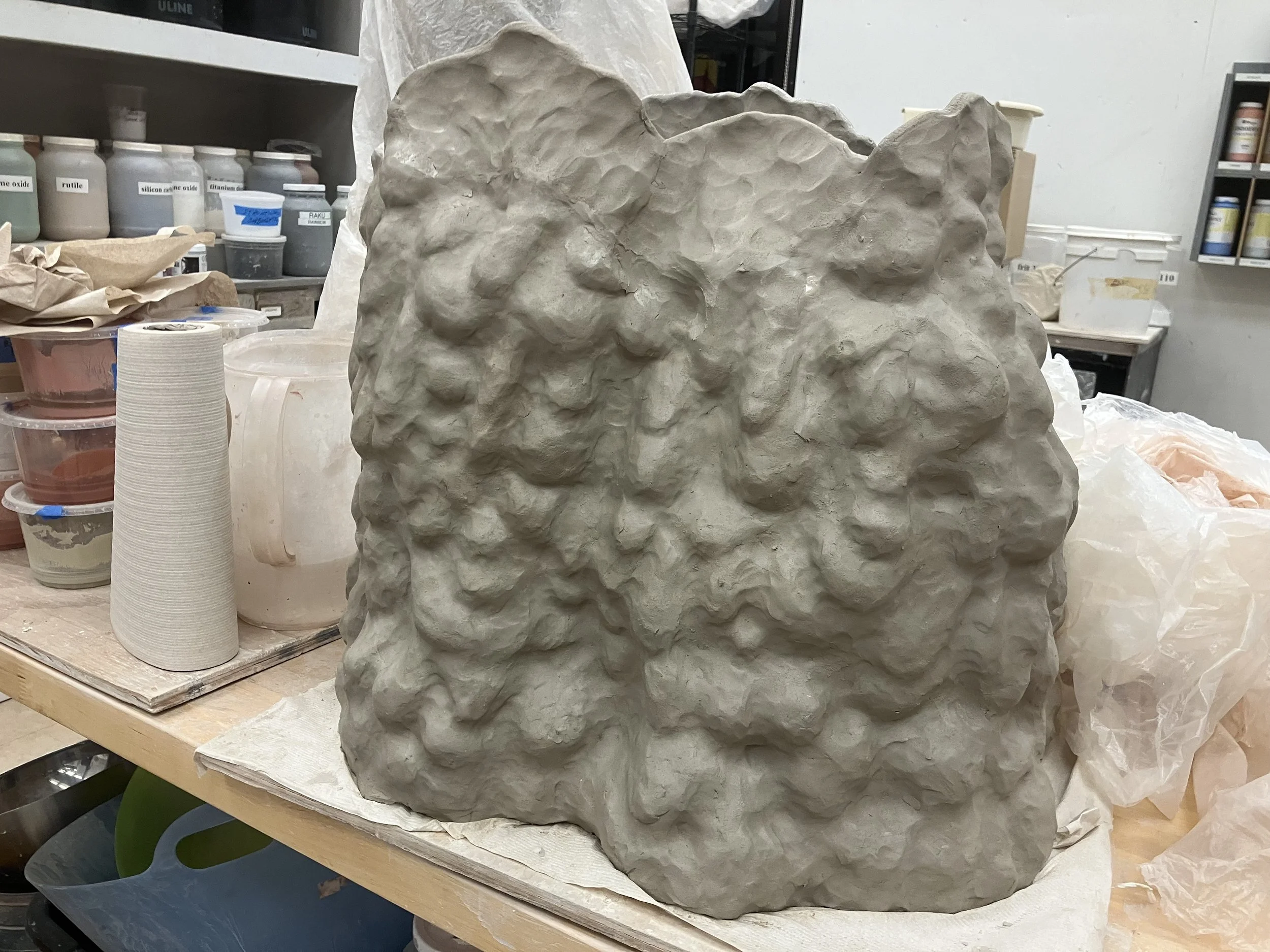

For years, I have been building figurative ceramic sculpture of women in wetsuits, thinking about this transformative moment of putting on or taking off a wetsuit, and inspired by the Scottish myth of the Selkie, a seal who zips off her seal skin to become a human woman. This year, I was trying to expand the way I think about ceramic sculpture— how can I sculpt the affective feeling of swimming? I had been reading a lot about hydrofeminism, and the embodied epistemologies of swimming. How can I render this in clay? I ended up creating these large, roughly human-shaped sculptures, using a coil building technique. The areas of the body not covered by wetsuits— faces, hands and feet, were rendered, everything else falling into an abstract, watery pattern. In texture and style, I was inspired by Shengwei Zhou’s beautiful ceramic sculptures and animations. These pieces required a lot of close attention to drying time in order to prevent them collapsing. I also learned a lot about the strength of clay, how to build internal supports, and to create a strong base for the piece. I used a clay type called Soldate 60 for the larger piece, and Sonora White for the smaller one. Soldate 60 was much easier to use, with more grog and stability.

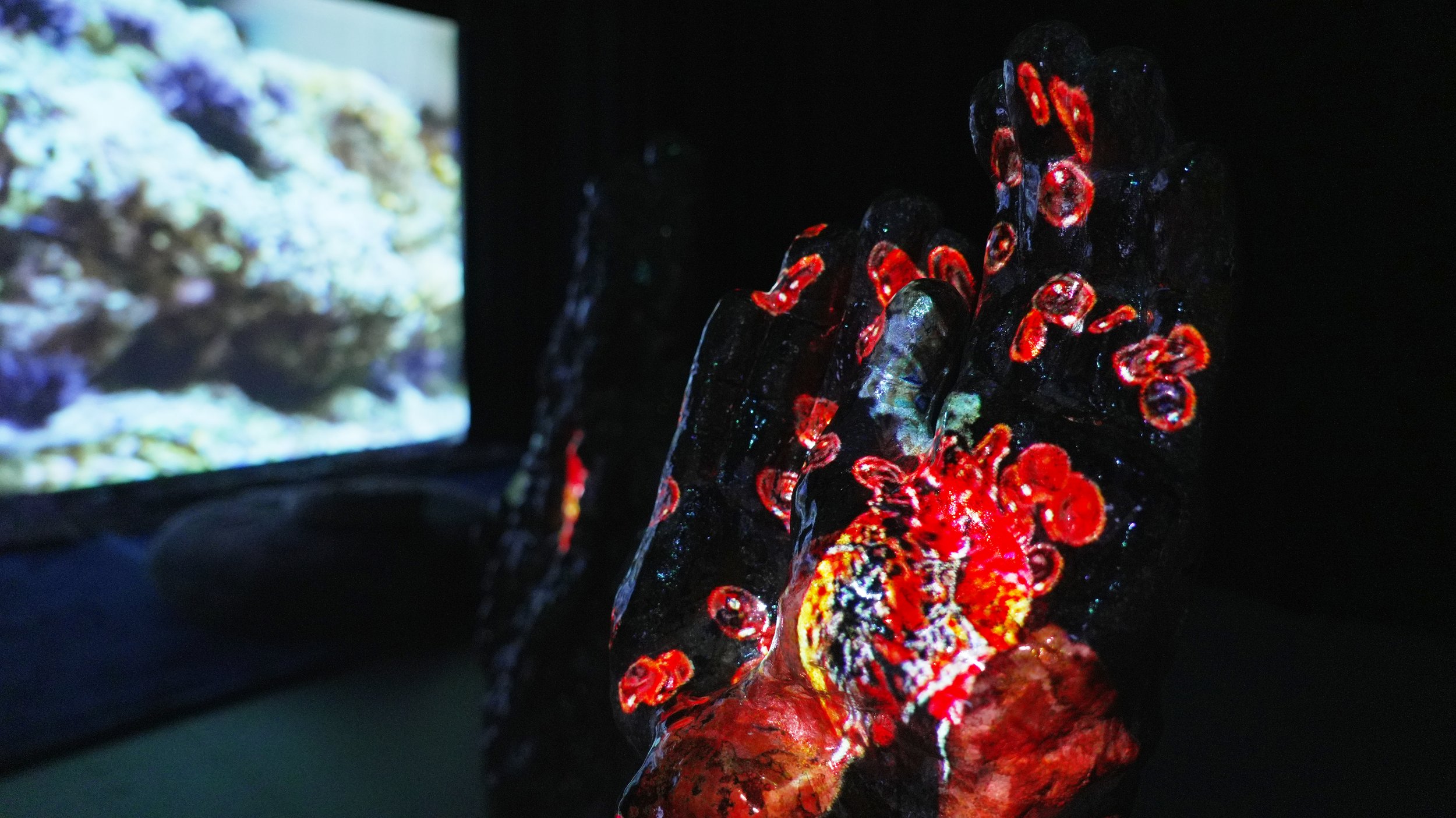

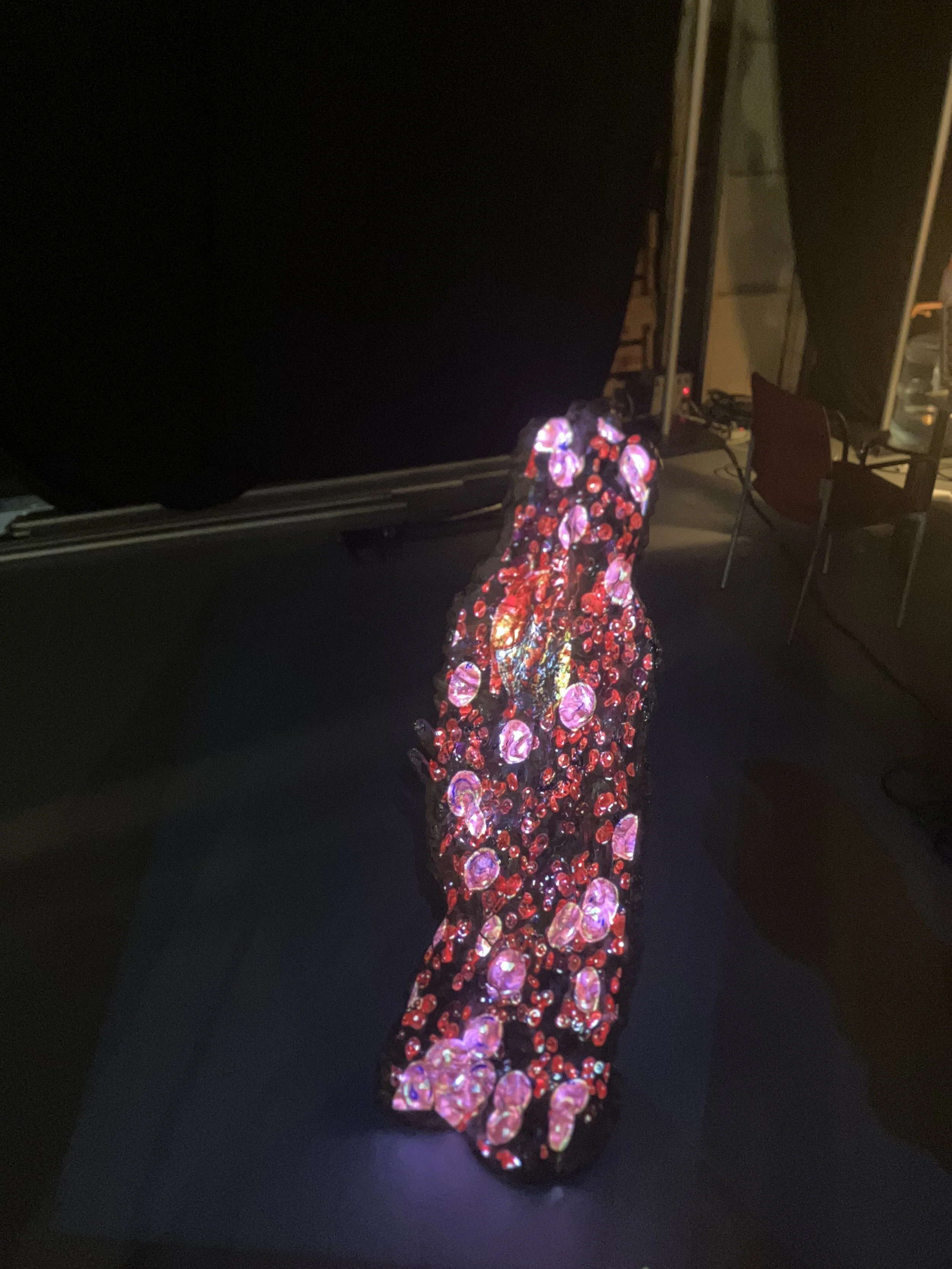

I treated the surfaces with several types of glaze, including something called Iron Blue, Red Iron Oxide stain, and a Celadon. All of these glazes are fairly dark colored, with the Celadon and the Iron Blue having mottled light spots. They were fired to cone 10, which gave them lovely dark, burnt colors. They warped quite a bit in the kilns, cracking minimally, and giving me a lot of information on further iterations. The entire process felt very experimental to me, trying on new techniques and aesthetic approaches. I really enjoyed the process, spending many hours in the studio with the other ceramic students, with a task that was both physically challenging and mentally simple. I was just coaxing the clay slowly to gain height.

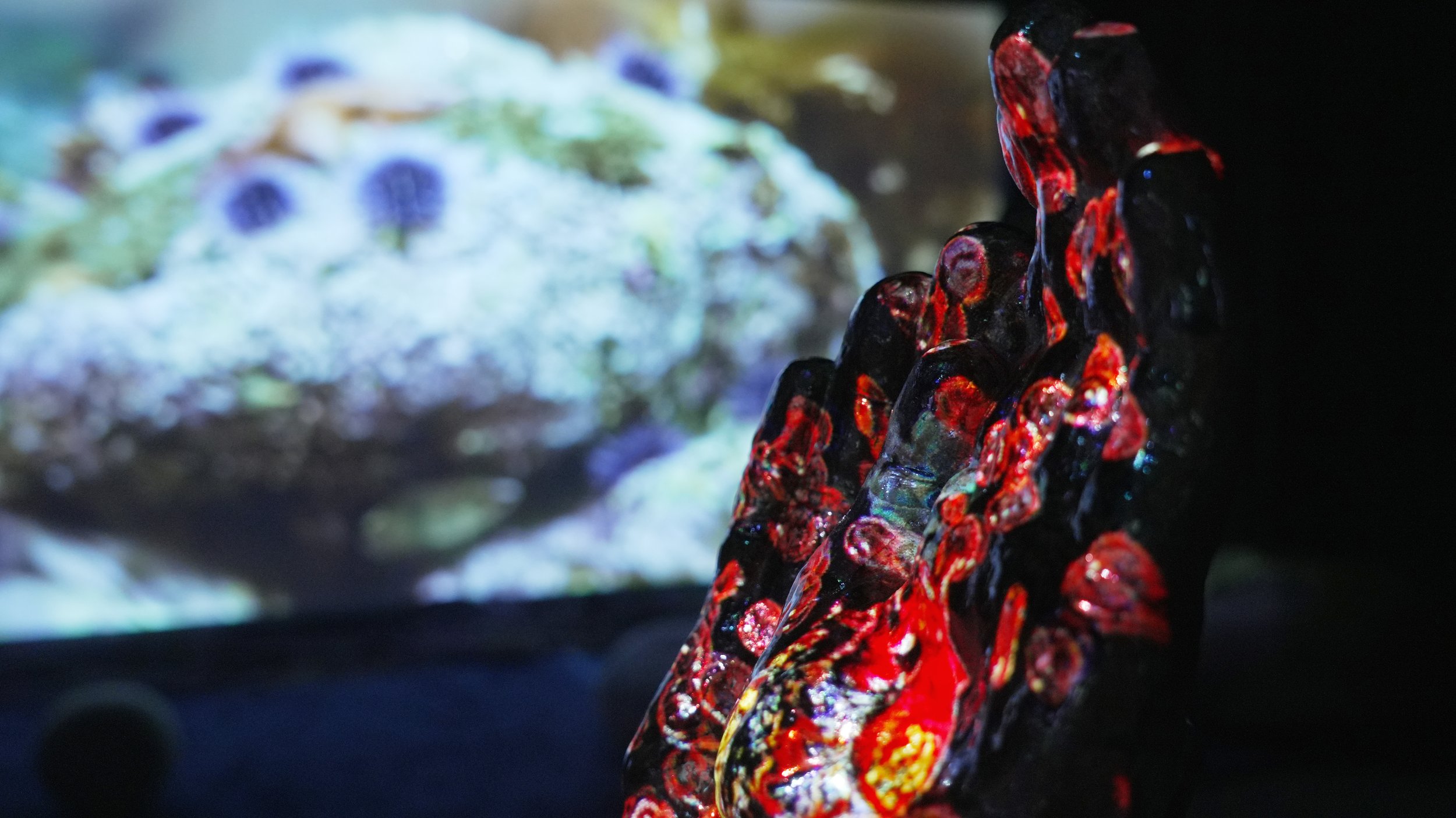

I challenged myself to combine video and ceramics. How does a sculpture’s finish, texture and curves add play or liveliness to a projected image? As projected light, the “3D” animations are the ideal medium to take the form of a physical surface. By releasing the video from being a screen, and wrapping it around a form, it becomes figurative, in-the-round. It has a presence.

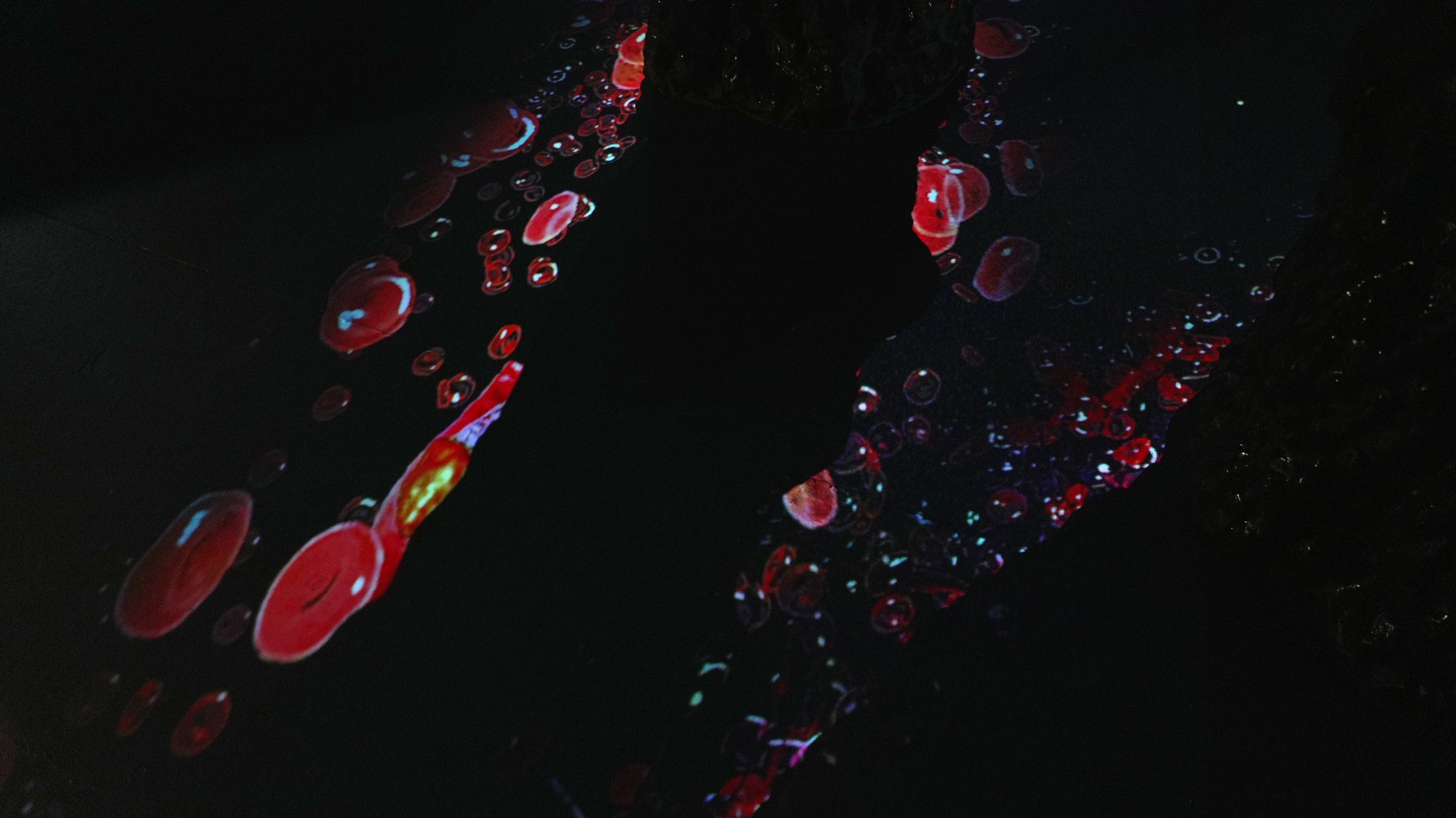

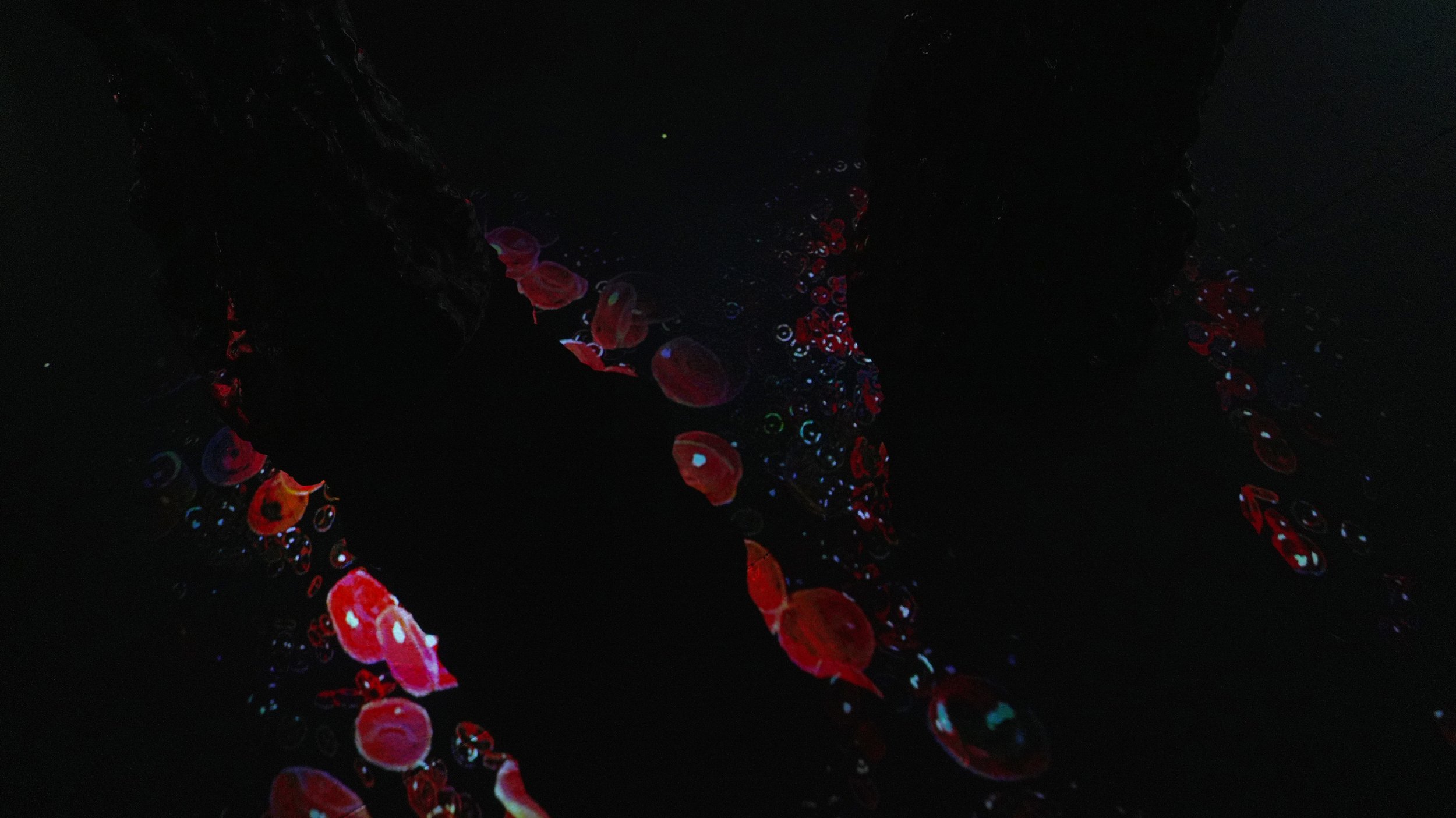

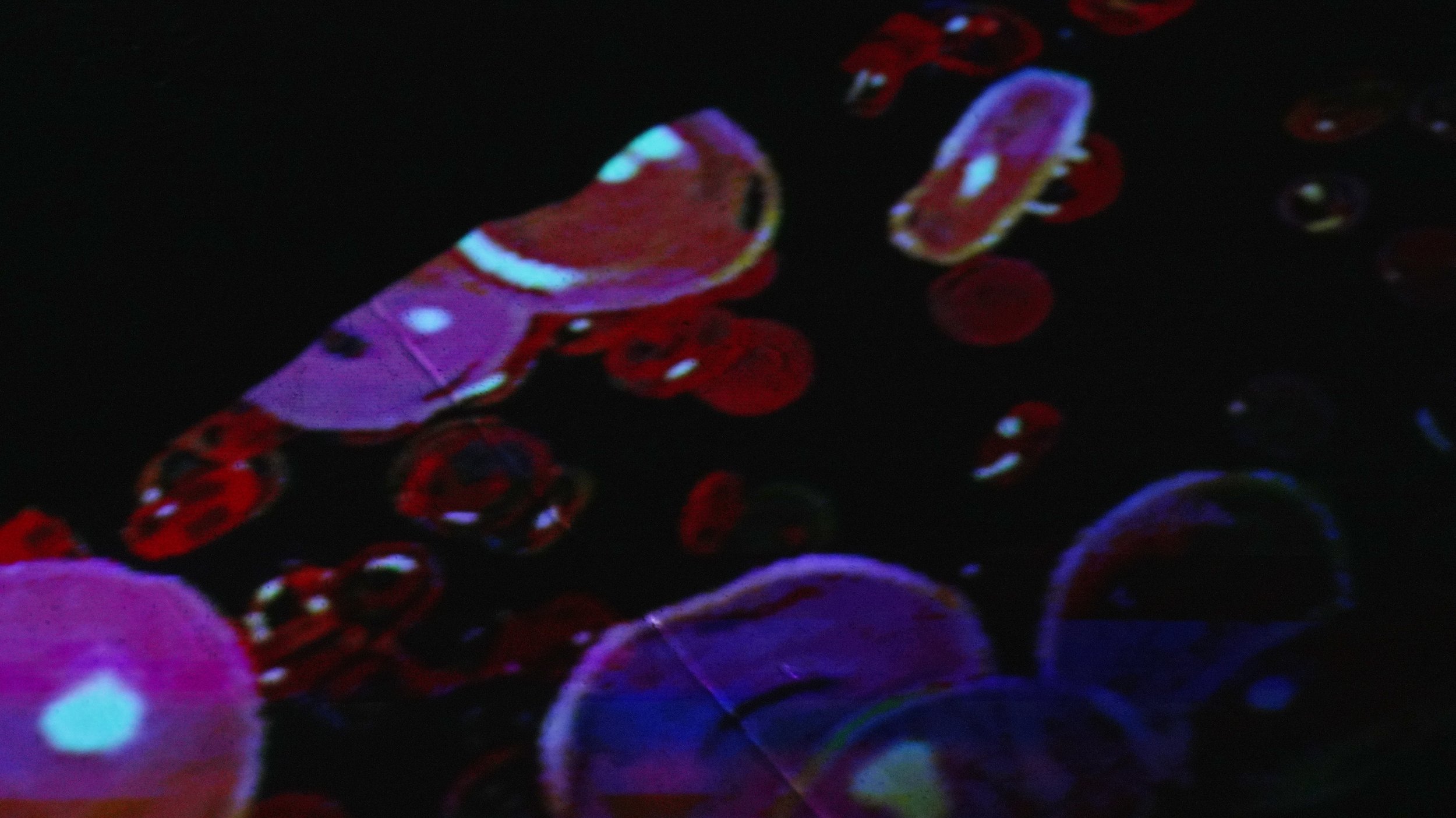

I wanted to test my new skills using Houdini modeling software to create animations that would dance on the surface of the sculptures. My knowledge of Houdini is still very elementary, but I was able to create some animations of the different physiological processes of the Mammalian Dive Reflex, in a poetic way, taking plenty of artistic liberties. To be specific, I animated a heart slowing down, a spleen spewing out red blood cells, a pair of lungs breathing and then remaining still full of air, and a pile of blood vessels constricting at the peripheries and expanding at the center. I also created an audio track, using found sounds to piece together a creative interpretation of the sounds of the inside of the body.

These videos were projected onto the sculptures in the gallery, allowing the animations to spill onto the gallery floor. Originally I had planned to carefully map the projections, but because the sculptures are so vertical, their shapes “mapped” the projections and separated them from the background. The spilling animations on the floor I felt were more appropriate to gesture towards the ideas of dissolving and transformation that I was thinking about.

The pieces were shown with the same animations projected onto them, staggered so they would not show the same animations at the same time. They were staged together with a piece that Zeynep Abes and I worked on together, a video installation called Kelp Dreams. The audio for Kelp Dreams, hydrophone recordings and above water recordings from around Southern California, I felt complimented the sculptures and their animations well.

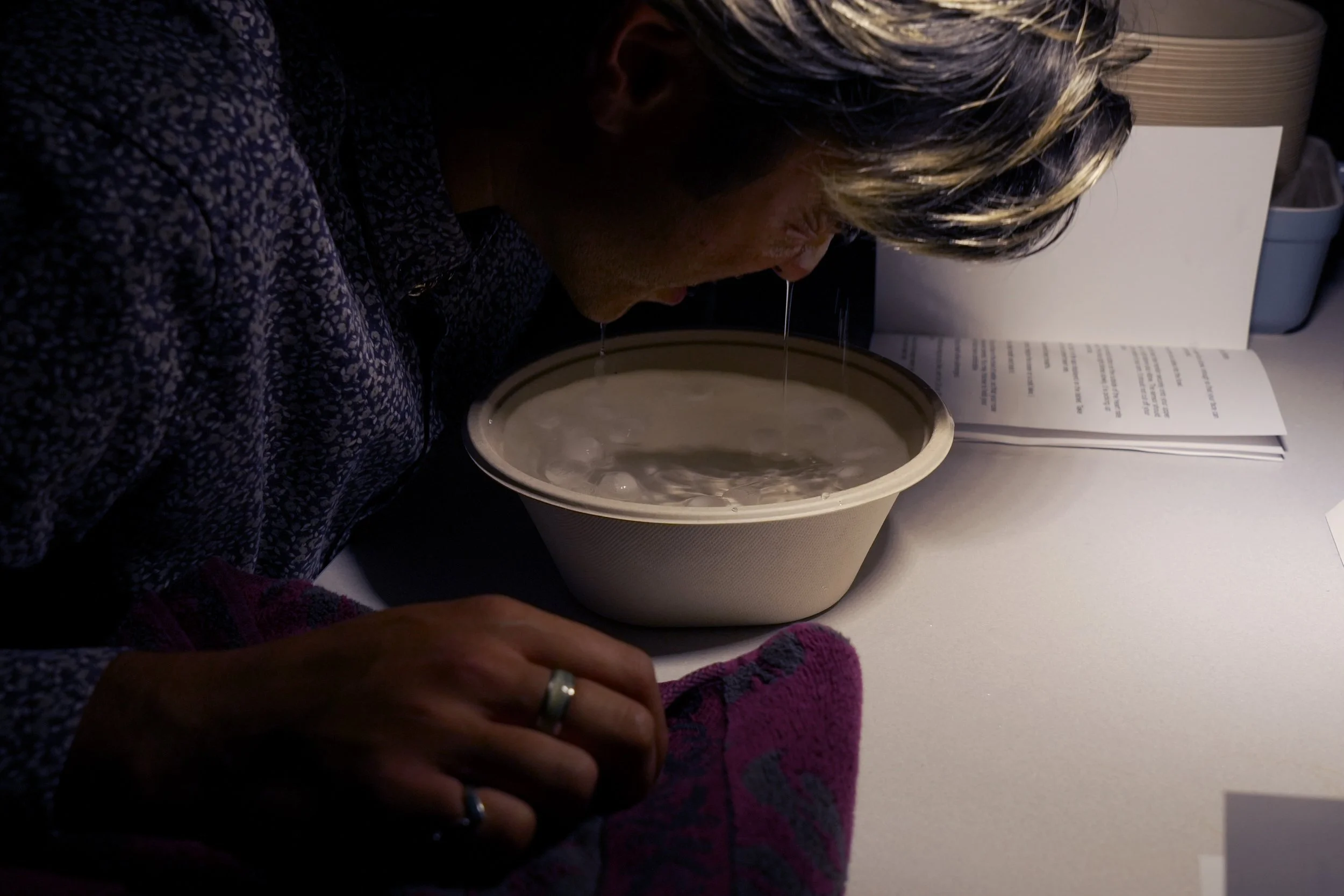

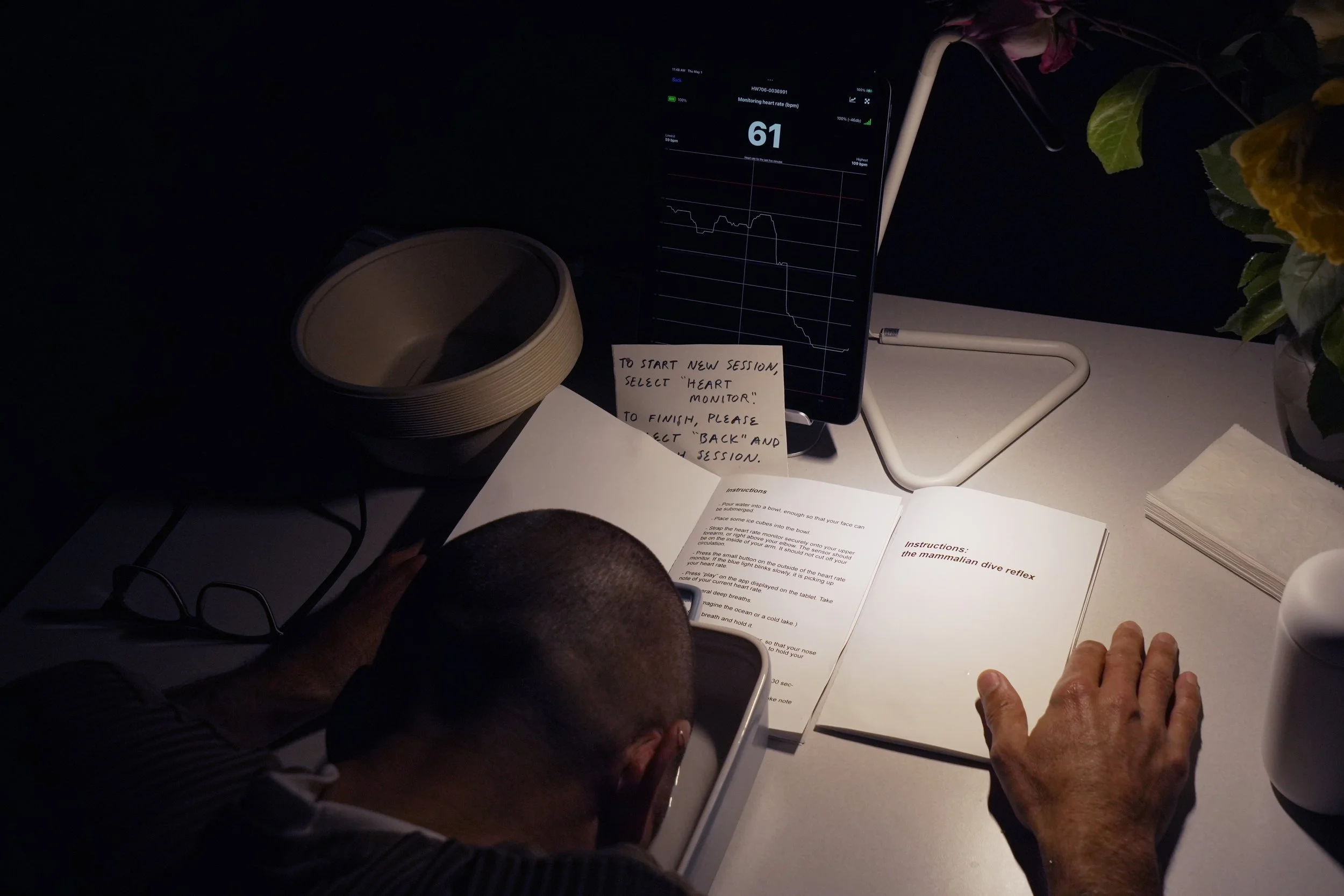

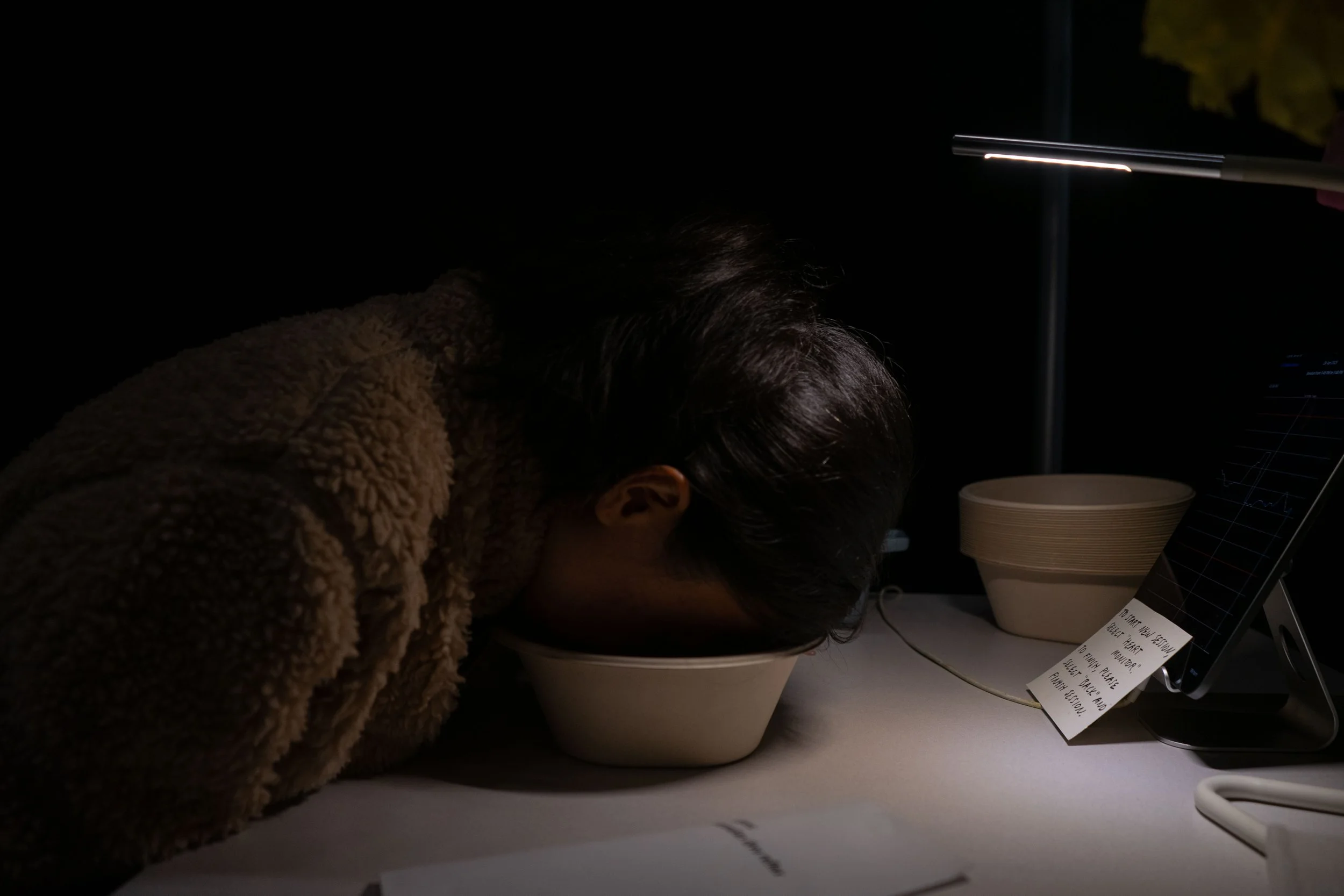

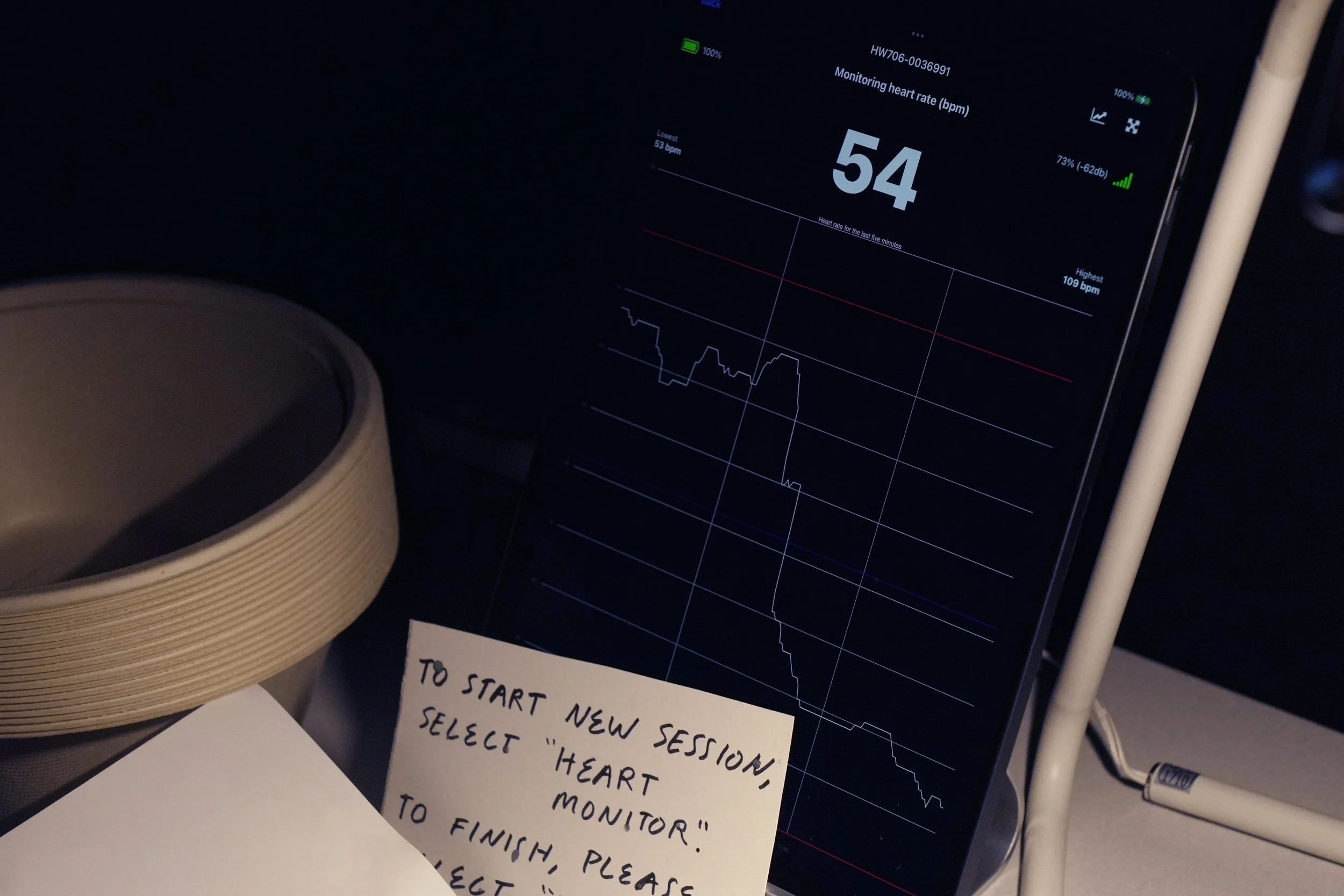

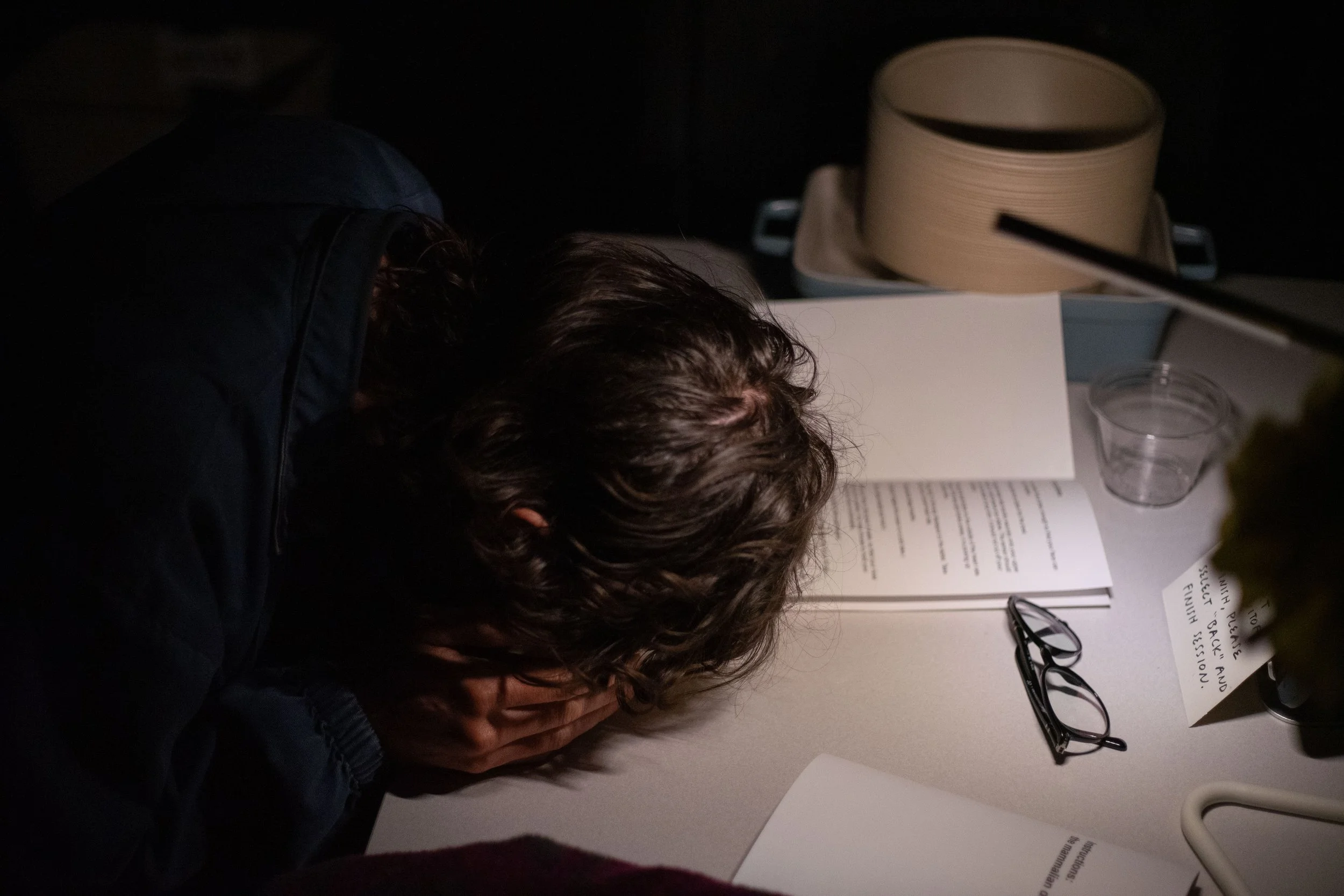

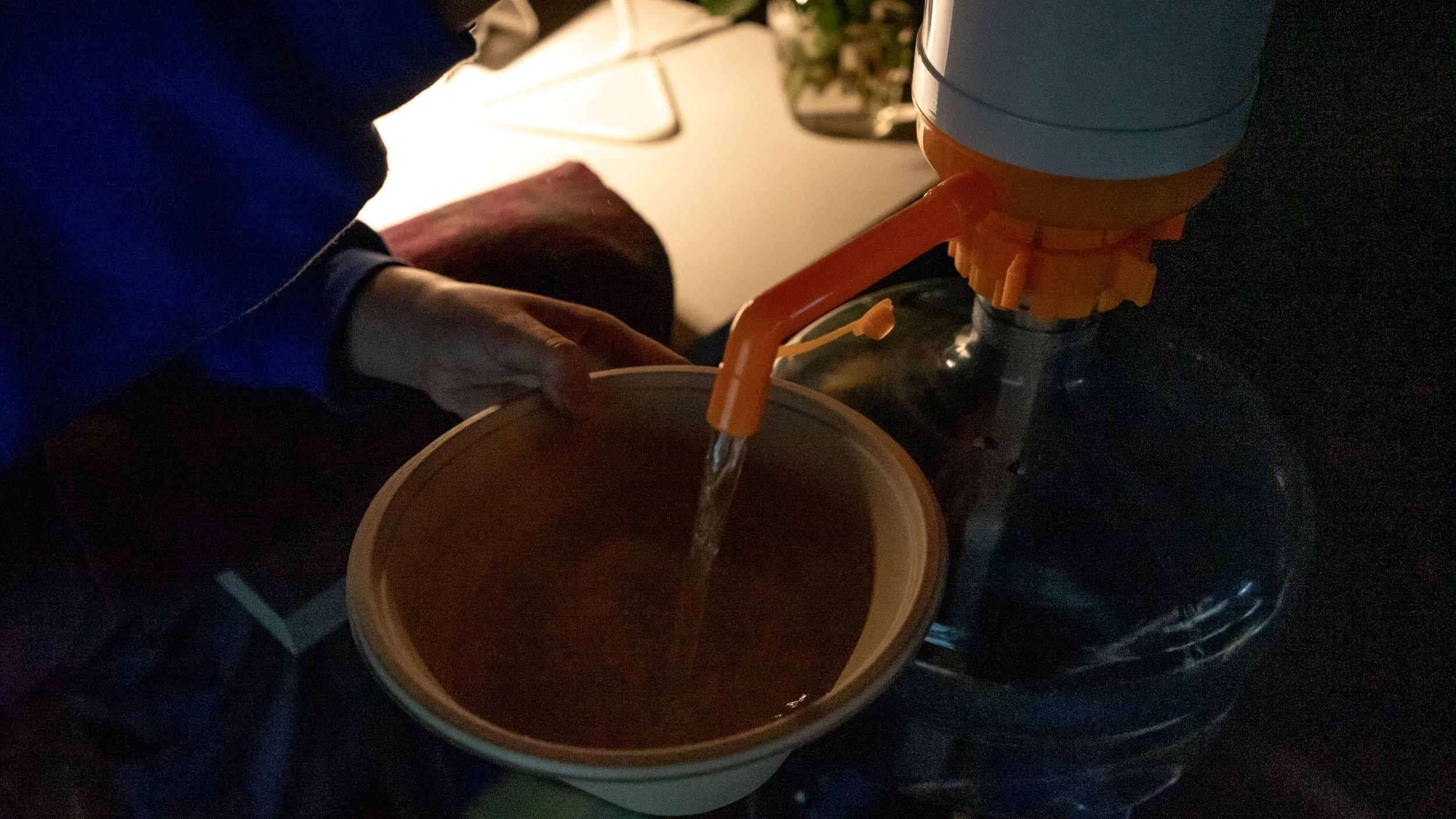

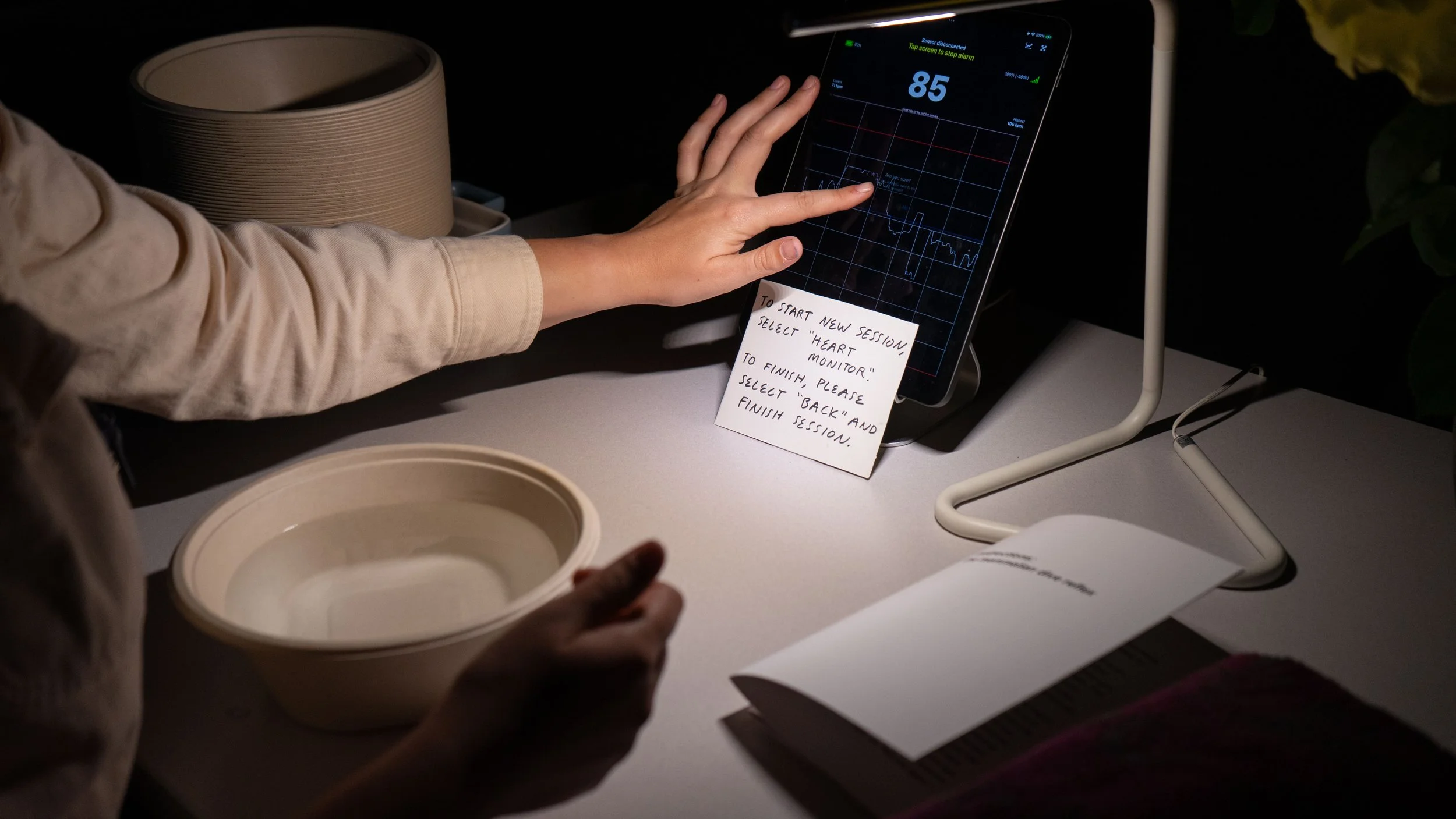

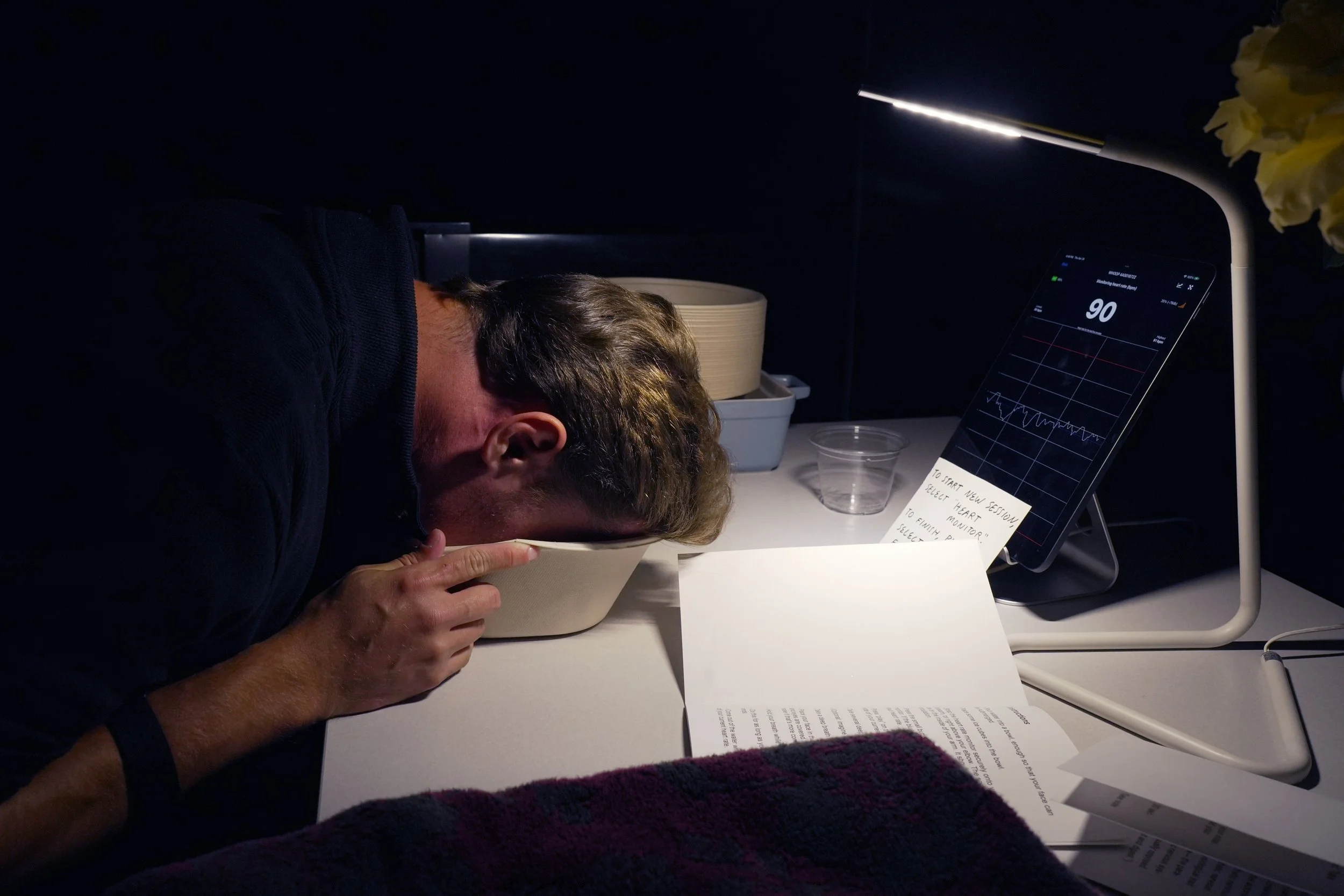

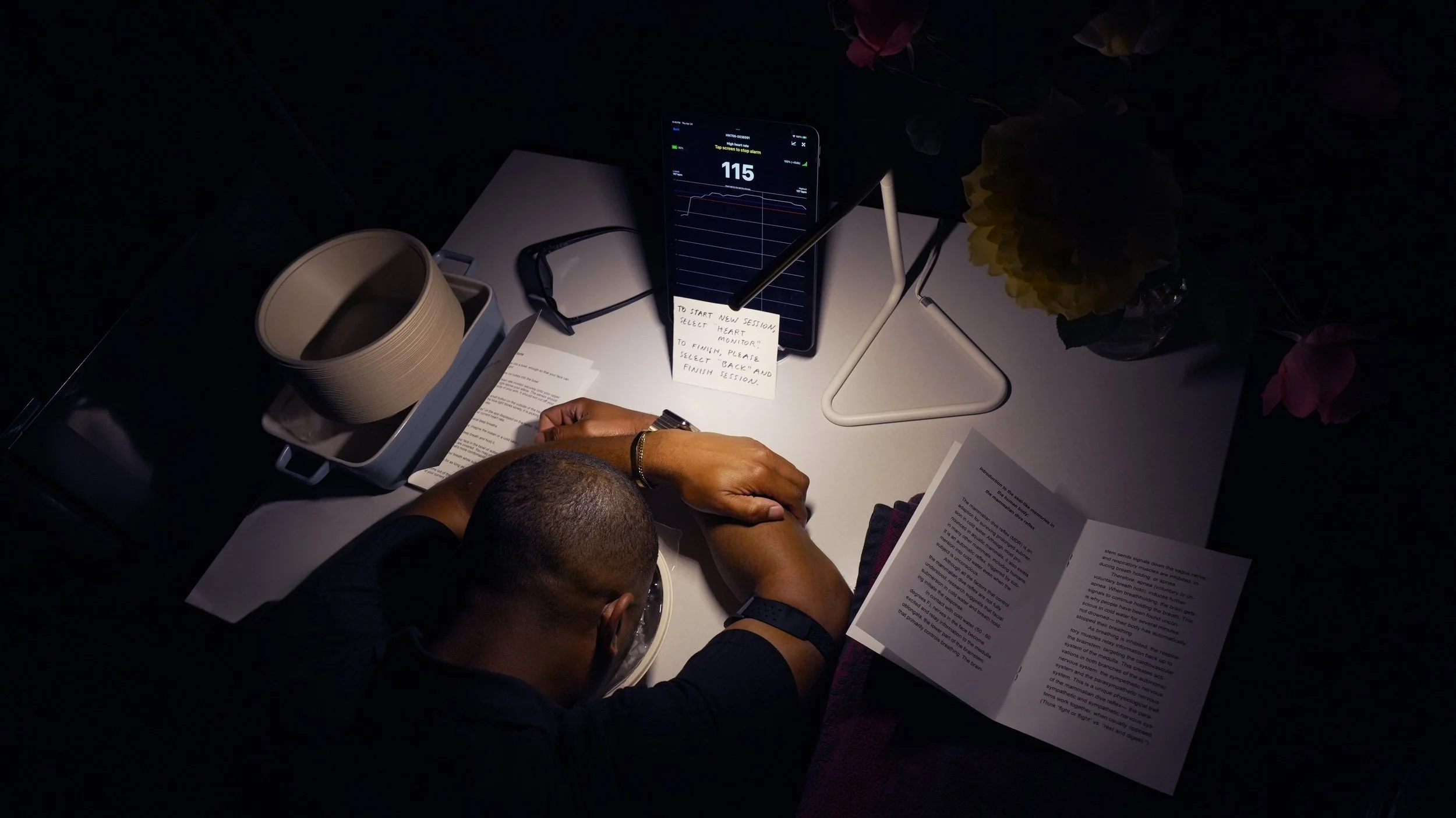

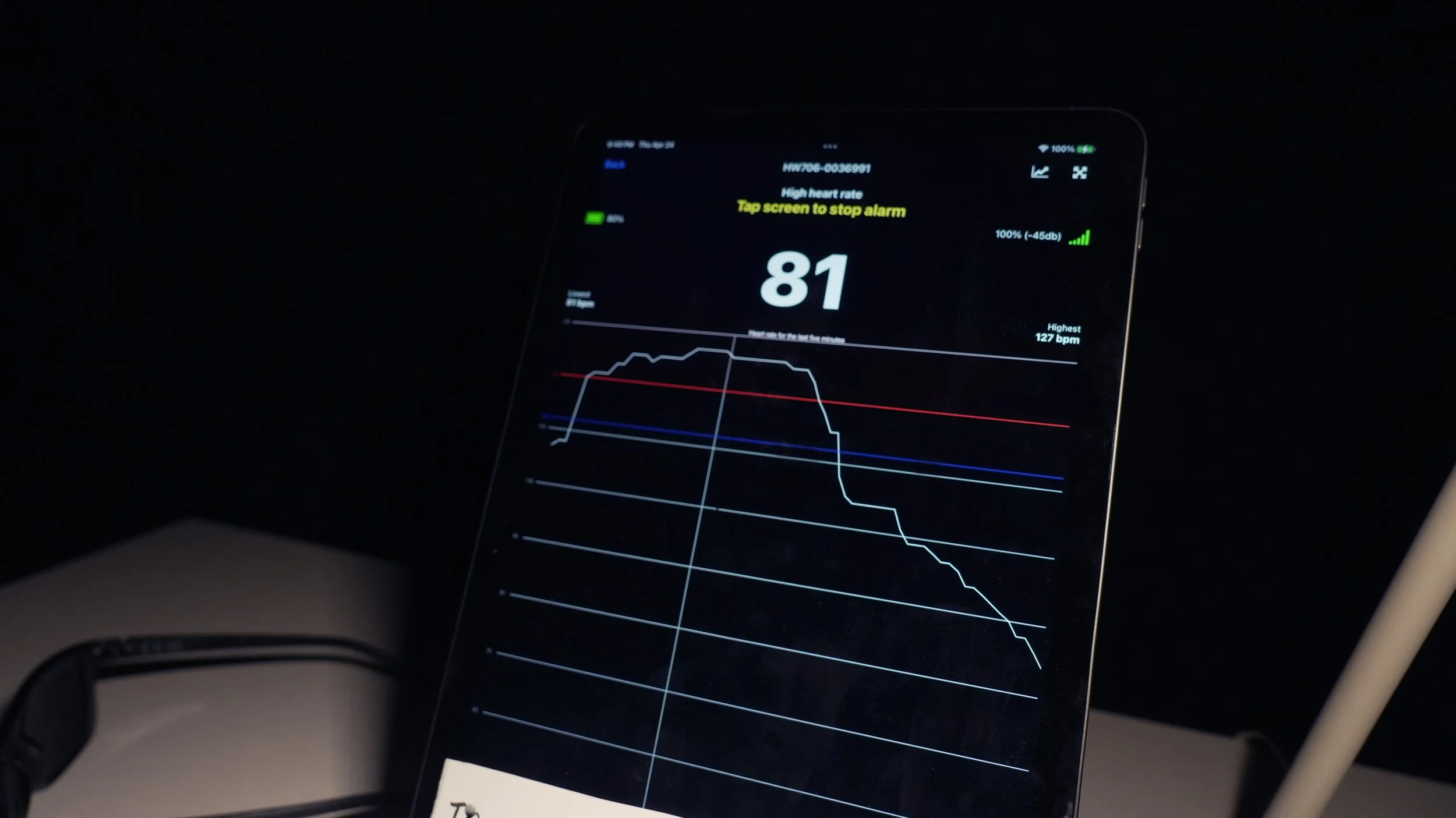

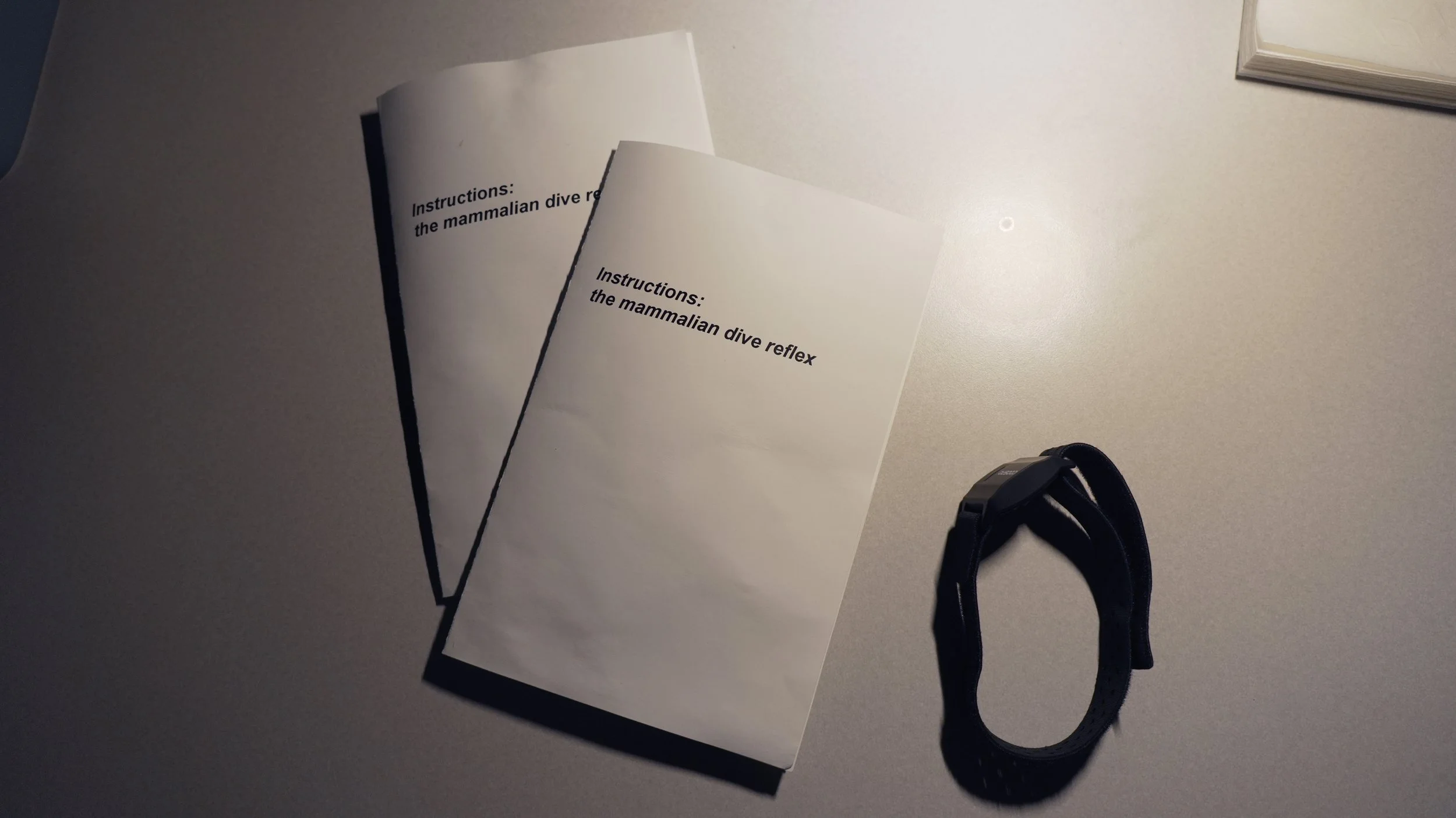

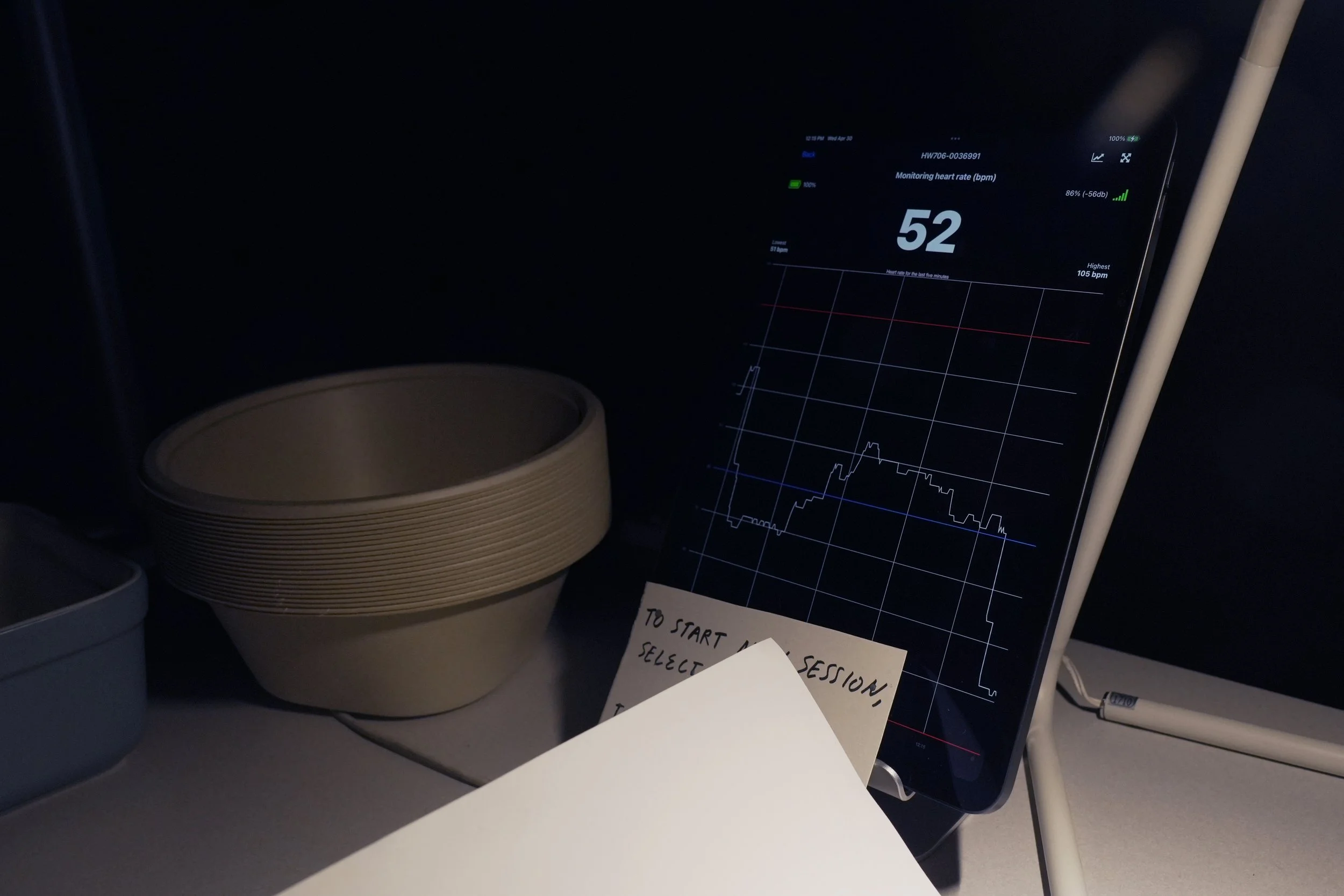

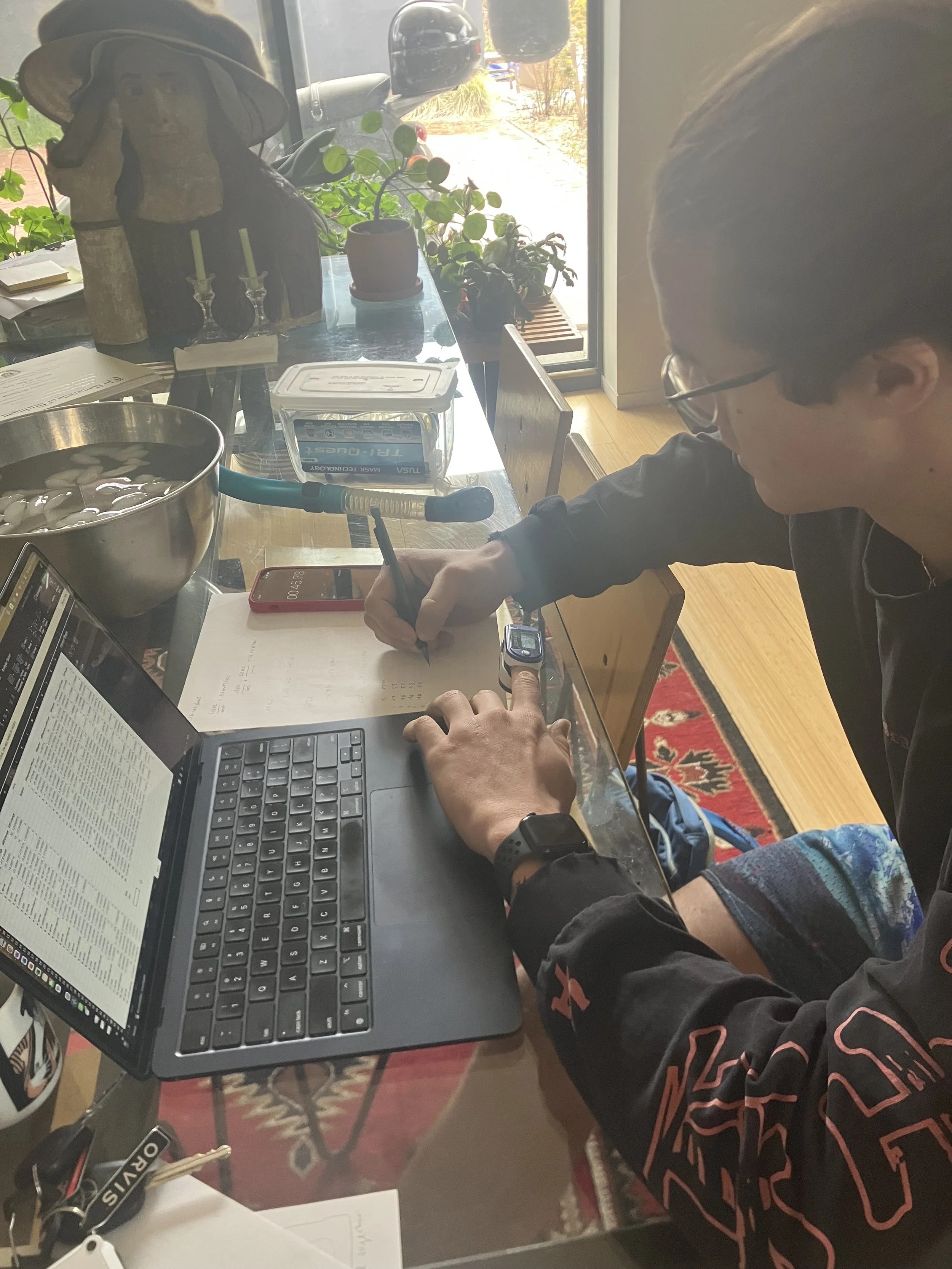

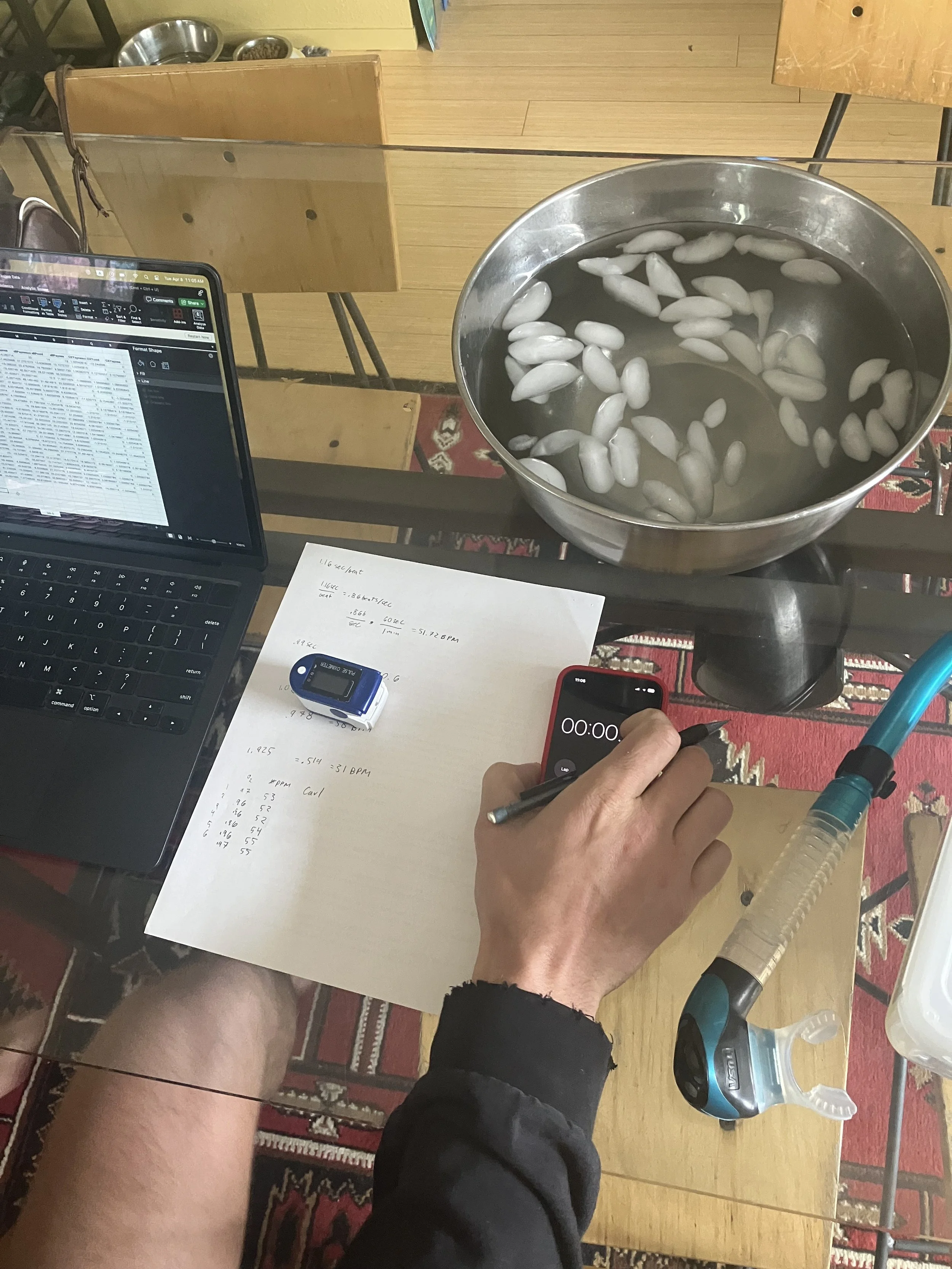

I also included a station where viewers could experience their own Mammalian Dive Reflex in real time. I set up a small desk, equipped with a reading light, a tablet with a heart rate monitoring app, a strap-on heart rate monitor, a freezer with ice, a water dispenser, and large bowls. Viewers were able to sit down at the desk, don the heart rate monitor, see their resting heart rate on the tablet, and then fill a bowl with water and ice. The viewer was invited to place their face in the water while holding their breath for a few seconds, and then afterwards, to see the change in their heart rate. Some people experienced very dramatic heart rate drops, while others did not experience any. In further iterations of this work, I think it would be interesting to have a log, where people can write down the change that they experienced. As it was, it created a bit of a voyeuristic effect, where other people in the gallery could have a window into someone else’s physiology.

Together, the installation was called, Let your eyes adjust to the new colors, it just takes some time. It felt like an experimental step into a new area of practice and creative work for me. I am looking forward to continuing to develop this work.